Chairman Pai Doesn't Know How to Measure Investment

Original photo by Flickr user GOTCredit

FCC Chairman Ajit Pai is trying to gut Net Neutrality protections at the agency by claiming they’ve stifled broadband investment.

Last week, Free Press released the comprehensive report It’s Working: How the Internet Access and Online Video Markets Are Thriving in the Title II Era, which proves that Pai’s claims are completely bogus.

We’re publishing a four-part blog series to expose his investment lies one layer at a time. In our first post, we explained how Pai is wrong on the numbers.

But even if Pai had done his math correctly — or rather, if the lobbyists he’s copying from had done their math correctly — the metric he’s using to evaluate the broadband market is inadequate and often misleading.

Investment is cyclical

Chairman Pai has insisted that aggregate broadband-industry investment has been on the decline since the FCC passed strong Net Neutrality rules under Title II authority. That argument is wrong on its face (aggregate investment is actually going up).

But it also relies exclusively on aggregate investment data, which are, at best, only mildly informative.

Let’s break that down.

Aggregate investment measures the total capital spending of all broadband companies in the marketplace, then calculates the industry’s percentage growth, combining a variety of individual results into a single data point.

That can be a useful starting point for analysis, but it glosses over variations between individual companies.

When we’re talking about investment, those individual developments are especially crucial because investment is cyclical.

Each company operates on its own unique cycle: It invests in building new infrastructure for a certain length of time, then switches to “harvest mode” and reaps the benefits of that investment while planning the next phase.

Capital spending is meant to fluctuate from year to year as companies complete upgrade projects and start new ones. Aggregate data, examined on its own, obscures this variation.

Technological developments also mean that for many internet service providers, it’s getting cheaper to expand capacity and upgrade their networks.

For example, once cable companies have already deployed a new cable line, they increase capacity primarily by upgrading the electronics at each end of the line. As technology improves, those electronics get better and cheaper.

Cable companies may see a decline in their capital investment not because they’ve stopped upgrading their networks, but because innovation is making it cheaper for them to do so.

In other words, ISPs may be spending less while still making their networks faster.

That sounds like good business to us, because no company’s goal is to spend as much money as it can — and more money than it needs to — just to prove to people like Chairman Pai that it’s truly investing enough.

So, aggregate broadband investment didn’t decline after the FCC voted to protect Net Neutrality. But even if it had, the aggregate dollar value of capital investments alone tells us nothing about industry infrastructure and capacity growth.

The right way to measure investment

The only way to get the complete picture is to conduct a comprehensive review of individual providers’ investments, deployments and offerings.

So we did.

What we found was a variety of stories — none of which suggests that Title II had any negative impact on network investment.

Across the board, 2015 investment results held close to the guidance companies gave prior to the FCC’s vote earlier that year, and 2016 results continued those trends based on each provider’s deployment schedule.

Two-thirds of publicly traded ISPs saw capital spending rise in the two years after the FCC vote.

Comcast’s cable investments increased nearly 27 percent during the two years following the FCC vote compared to the two years prior. In 2016, Comcast spent $7.6 billion on its cable segment, the most it’s ever invested in a single year. Most of this spending increase stemmed from new deployment and the accelerated rollout of advanced network infrastructure for gigabit-capable broadband service and next-generation pay-TV services.

It wasn’t just the biggest ISPs that spent more after the Title II vote.

In 2016, Alaska-based General Communications Inc. (GCI) also reported the highest capital spending in its history, which came from reinvesting tower-sale proceeds into new fiber-network deployment. GCI expects its spending to decline in 2017 after it completes that deployment project.

It’s noteworthy, however, that GCI — a small provider serving mostly rural and remote territories — continued its planned deployment cycle without any discernible impact from Title II.

Some providers actually exceeded their own investor guidance, completing upgrade projects sooner than expected and investing more than initially planned.

Mediacom dramatically increased capital spending to roll out gigabit capability to its entire footprint. It had planned to finish that project within three years, but actually completed it in just one year.

Cincinnati Bell continued expanding fiber service and spent a whopping 50 percent more on capital investment in the two years following reclassification than in the two years before the FCC vote. The company predicted that 2015 would be its peak investment cycle, but it invested even more in 2016.

Several providers did see declines in capital spending in 2015–2016, but it’s clear from those companies’ own guidance and their deployment efforts that this had nothing to do with the FCC restoring Title II. In most cases, it wasn’t even a sign of lagging deployment.

AT&T is the most important example of this.

Its overall capital expenditures declined in 2015 due to the completion of “Project VIP,” which included a major LTE expansion on its wireless network and significant wireline upgrades. This project raised AT&T’s capital spending significantly during 2013–2014; then spending declined to more normal levels after that, just as AT&T promised investors it would more than two years before the FCC’s vote.

Now the company is telling shareholders to expect another increase in capital spending as AT&T accelerates fiber deployment and prepares for 5G.

Contrary to what Chairman Pai and the industry-funded studies he cites would have you believe, AT&T’s temporary dip in investment doesn’t mean Title II reclassification was crushing its business. Rather, this was a natural part of the company’s investment cycle.

Other companies with decreased investment in the two years following the FCC’s vote lowered their spending for similar reasons.

A year after reclassification, Altice announced a five-year plan to upgrade its entire footprint with fiber technology capable of delivering 10 gigabit speeds. Yet Altice still estimates its capital spending will decline thanks to a variety of cost-savings the company expects to reap from its prior investments and technological leaps.

This process is already in motion: Investment declined in 2016, but subscribers to Altice subsidiary companies Cablevision and Suddenlink saw significantly expanded network capacity. CenturyLink, like many legacy telecom companies, has seen capital-spending declines as it’s struggled to compete with dominant cable networks, but it recently began major investment in next-generation network technologies.

For an in-depth look at each provider, click here and scroll to Part III of It’s Working.

If the FCC’s vote to protect Net Neutrality under Title II had truly hampered investment, we would see a systemic effect depressing deployment and buildout across the industry.

Instead, we didn’t find a single instance in which a company cited Title II as a factor harming growth. Most companies spent more than they had before the vote, and some spent less, but such declines weren’t due to Title II — and aren’t the least bit out of the ordinary.

Despite all of Pai’s bluster, it’s simply not true that capital spending must always go up.

Moreover, capital spending isn’t the only measure of industry growth and success.

It would be irresponsible for a doctor to diagnose a patient after checking just one potential symptom. It’s just as irresponsible for Pai to diagnose the broadband industry as stagnant without looking at other important growth indicators, including revenue, subscriber totals and profits.

Internet access is an increasingly essential service fueled by rapidly evolving technology and offered in a marketplace with very little competition. It should come as no surprise, then, that providers continue to enjoy rapidly growing revenues. Total revenues for publicly traded ISPs grew at a compound annual growth rate of 5 percent during 2013–2016.

As with aggregate investment data, aggregate revenues often overshadow important differences between individual firms and types of companies. For example, over the past four years, cable companies saw their revenues increase at a rate of 5.6 percent, more than three times the revenue-growth rate of 1.8 percent for legacy telephone providers.

These company-wide aggregates may include revenue from other services the companies provide.

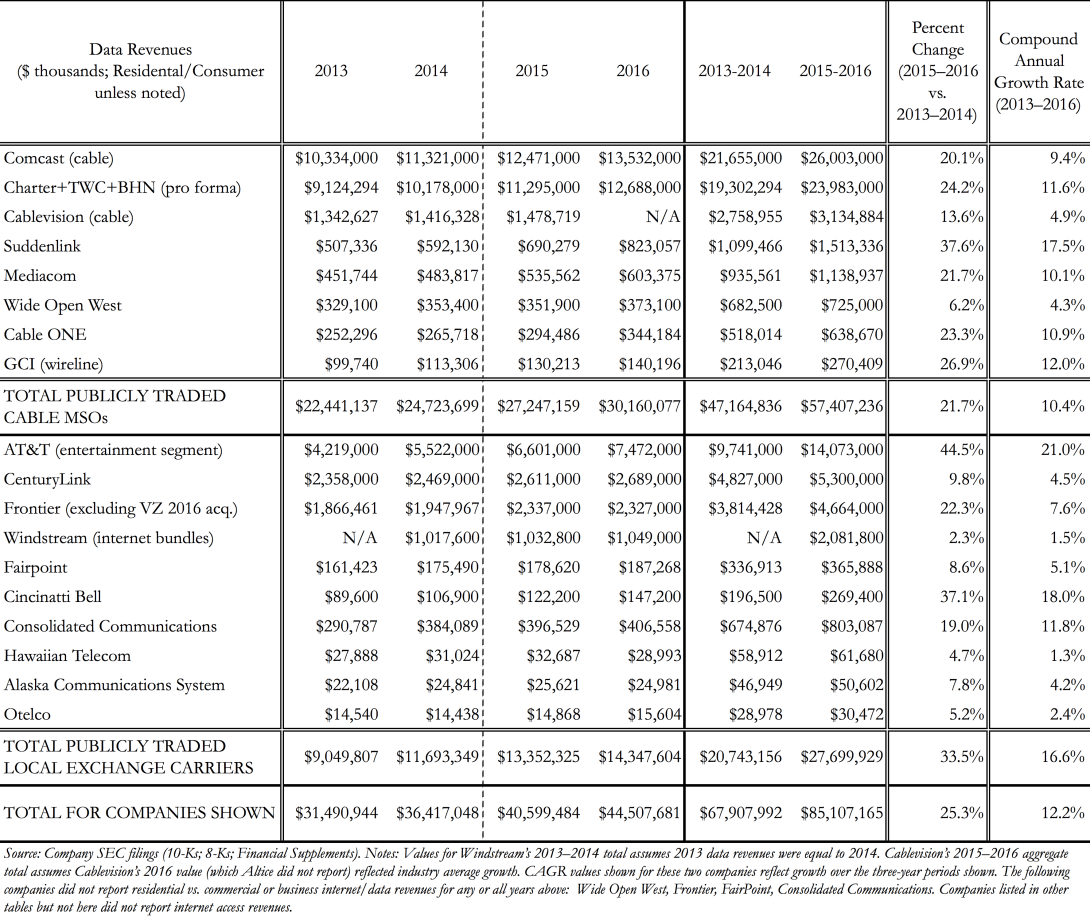

To get a better sense of how consumer-broadband businesses are faring in isolation, we also examined their reported residential internet or data revenues during 2013–2016, shown below in Figure 5 from our full report:

On the whole, broadband-revenue growth was significantly higher than the growth in overall revenues, with an industry-wide growth rate of 12.2 percent.

That suggests that for many companies, broadband service is a revenue leader used to subsidize losses or less substantial growth in other services. Far from buckling under the weight of Title II regulation, the broadband market is leading the charge in making money for these communications conglomerates.

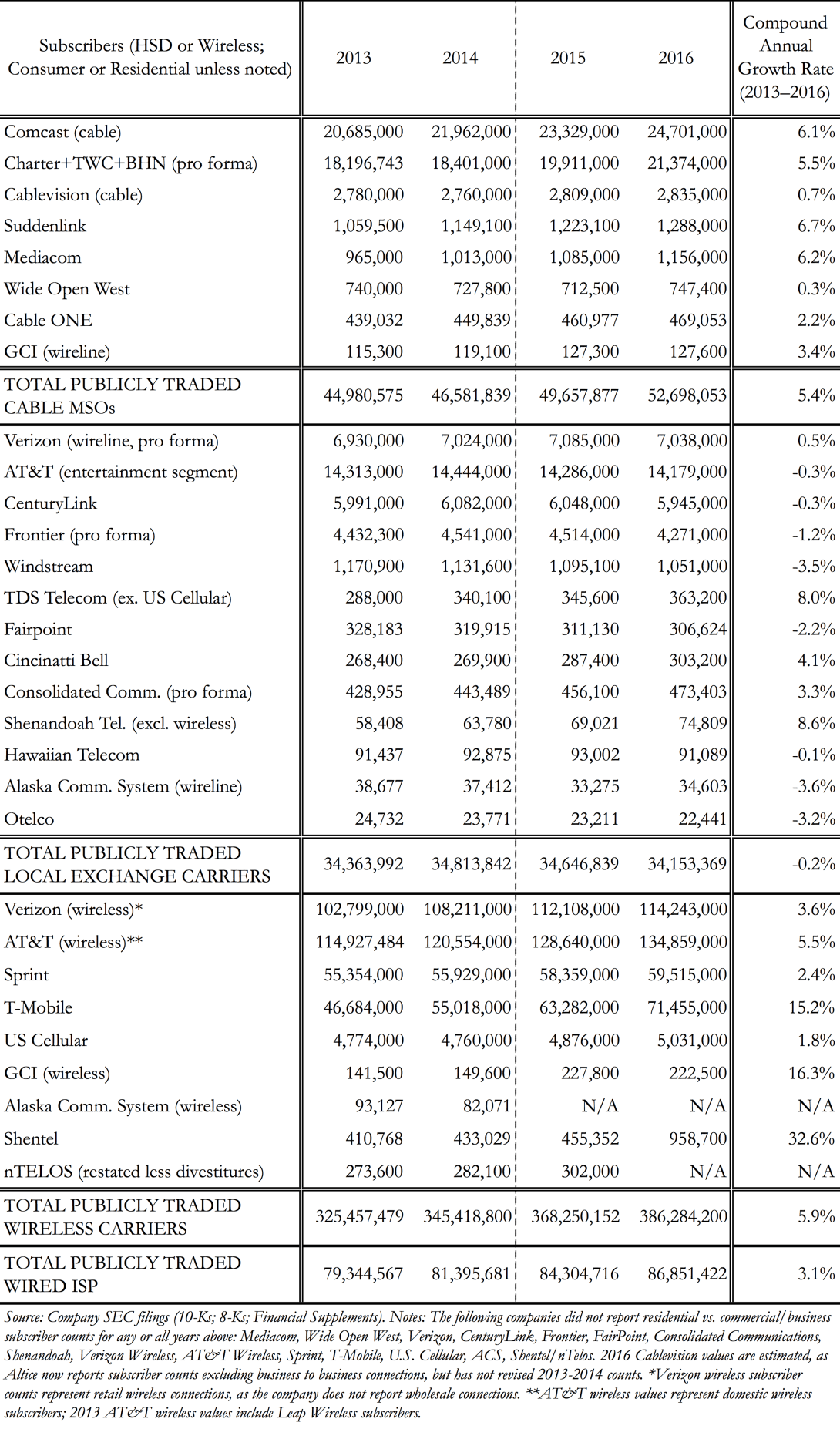

Subscriber totals also grew during the past four years, with wired internet providers reporting a subscriber-growth rate of 3.1 percent and a wireless subscriber-growth rate of 5.9 percent.

Figure 8 from our report shows this growth for each publicly traded provider:

For the wired providers, most of those new subscribers went to cable companies rather than legacy telecoms, though the telecom companies that have invested in fiber and other next-generation networks generally experienced more subscriber growth than their counterparts that stuck with older, slower technologies like basic DSL.

Wireless-subscriber growth was particularly concentrated at the big four industry leaders: AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile and Verizon.

Notably, 33 percent of new subscribers went to AT&T, the company that Pai and his industry friends falsely point to as the main victim of Title II.

By every available measure, broadband-industry profits have also continued to grow in the wake of the FCC’s decision to reclassify internet access under Title II.

Operating cash flow at the publicly traded broadband providers was 5 percent higher in the two years after the vote than in the two years prior. Operating income at the top publicly traded providers increased 18 percent, and Wall Street’s favorite profit metric (known as “EBITDA”) increased 16 percent during the two years following reclassification.

When Chairman Pai repeats his hollow claims that Net Neutrality protections have stifled broadband investment, he’s willfully ignoring the complexity of individual companies’ deployment cycles, as well as their ongoing patterns of achieving healthy growth in revenues, subscribers and profits.

Even if his aggregate numbers added up, Pai is using the wrong approach to measure investment. Any analysis that, like his, ignores so many critical metrics is inadequate at best.

To learn more, click here for the full Free Press report It’s Working: How the Internet Access and Online Video Markets Are Thriving in the Title II Era.