'The Crisis in Journalism Underpins a Crisis of Democracy'

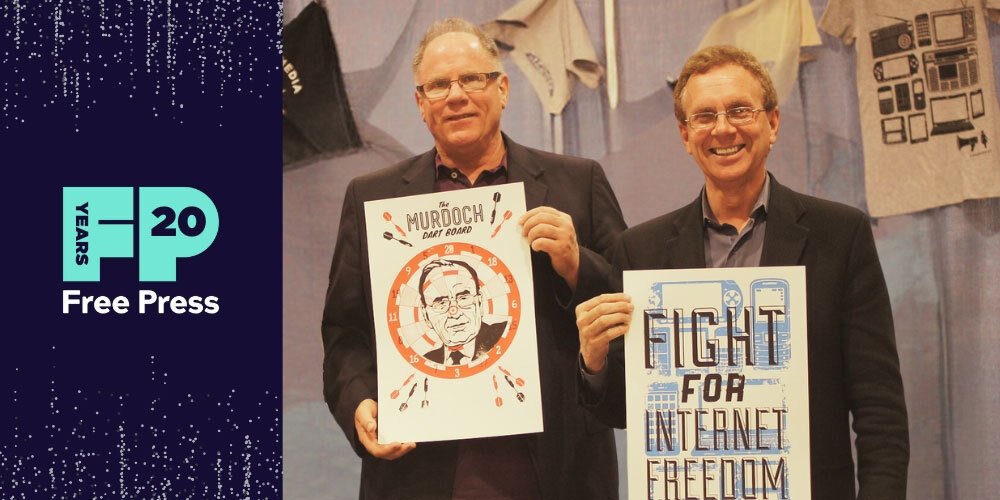

Free Press co-founders Robert W. McChesney and John Nichols at Free Press’ National Conference for Media Reform

Free Press is 20 years old. It wouldn’t exist without the insights, activism and intellectual inspiration of two of its co-founders, Robert W. McChesney and John Nichols. McChesney is professor emeritus at the University of Illinois. Nichols is the national affairs correspondent for The Nation. They have authored or co-authored more than 25 books on media and politics. I spoke with them via Zoom from their homes in Madison, Wisconsin. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The founding of Free Press

Craig Aaron: Let’s start with the two of you. Your relationship is such a big part of the origin story of Free Press. How did Bob McChesney and John Nichols get together?

John Nichols: It actually goes back to a Wisconsin public-television program. Bob had just won one of his many awards for writing a brilliant book on media, a stark critique. I think they presumed that the two of us would sit on this panel, and Bob would make his critique of media —

Robert W. McChesney: — and John was the hard-boiled city editor now coming into the Capital Times who was going to set me straight.

JN: So Bob laid out his argument, and they turned to me, and I said, “Well, it’s actually far worse than he says.” And from there, the interview kind of degenerated, and they didn’t get what they wanted. There wasn’t a clash. But we walked out of the studio saying, “Boy, you know we agree on elements of this crisis.” And that began a conversation that went on for several years, largely between us. I joke that Bob and I thought we were going to solve this problem quickly.

CA: How did this conversation turn into Free Press? What do you remember about that moment when things shifted from “people should get together to do something about this” to “people are actually getting together to do something about this”?

RWM: I wrote this book called Rich Media, Poor Democracy, which came out in 1999. That was the book that Josh Silver read. He basically introduced himself over the phone and said he was a guy who had been working on a campaign-finance-reform organizing campaign down in Arizona to get money out of politics. He said: “We’ve got to do something about this media stuff. I want to organize a group that’s going to raise these issues.”

John and I had been saying in our books that we needed to organize and make this a political issue. But he’s a journalist, I’m a college professor. We’re not professional organizers. Here comes an organizer who has had some success and has a lot of energy and says I want to organize on this issue, and I know how to do it. We set up a meeting in Washington a few months later with Josh, John and Janine Jackson from FAIR. We came up with the name Free Press.

CA: Why did you want to call the group Free Press?

RWM: You can’t have a free society without a credible press system. The Framers took that very seriously from the very beginning, with the postal subsidies that really spawned our press system. The name Free Press, we thought, would draw attention to the politics of setting up a press system. That the media was a legitimate political issue, and we had to take it seriously by demanding a “Free Press.” That it wasn’t just about “good news” or “news I like.” It was about setting up institutions that would generate what we need.

This is the conversation I had with Josh Silver. We were discussing calling it “Committee for a Free Press,” or something like that, and Josh smashed his hand on the table and said: “It can only be a two-word name! All successful groups, it’s only two words.”

I said, “Then Free Press it is.”

Throwing off the training wheels

CA: What other memories stand out from when you were forming Free Press?

JN: In early 2003, we got invited to go on Bill Moyers’ show, which back then was a big deal on PBS. We went to New York to do this, right? For us, that’s a very big deal. We get on an airplane. We’re like kids with our bags going to the big city. We went to New York, and we were on the set assuming it was going to be a short interview.

I remember Moyers was signaling to his crew — keep it going, let’s keep doing this. And it extended into this much longer interview than we had initially anticipated. Moyers’ interview was stellar, it went right to the heart of the matter, right to the core issues. Bob talked in deep ways about the structural realities of the media and the challenges that existed. And Moyers mentioned this pamphlet we had just published.

The night that it aired I was at a party with some friends, and I got this call saying, you should look at what’s going on at Amazon. If I’m not mistaken, I believe the pamphlet went to No. 3. It went incredibly high in national sales, and we sold out. What we suddenly realized was this movement that we wanted to create, that we thought was going to take a very slow process of organizing, had suddenly hit a moment. And so then Free Press became … this urgent reality. We were needed immediately.

CA: By the end of that year, Free Press was an organization. Kimberly Longey had come on board and helped hire the initial team. And right away Free Press was rallying the public and holding its first National Conference for Media Reform in Madison.

JN: When we announced the conference, we thought maybe we’d hold it in a high-school gym or something. But all sorts of people started to say they were going to come. Naomi Klein. Studs Terkel. Bill Moyers. Ralph Nader. Members of Congress like Sherrod Brown and John Conyers. And so suddenly, our movement already seemed bigger than we had imagined it would be.

RWM: That conference was extraordinary, and people who were there will never forget it because it was so unexpected. It was like Woodstock, in the sense that they expected 10,000 people and suddenly half a million showed up. We didn’t have the same numbers, but we didn’t know what to expect. Every venue was packed to the gills all over the campus.

JN: There was such an energy, such a passion. I can’t emphasize enough how much the war in Iraq was essential to this. I remember being on stage reading messages from around the country and around the world cheering on what we were doing. And there’s this crowd of 1,800 people on their feet, all excited. One of the things we got was a message from a soldier in Iraq who sent an email basically saying, look I’m over here and this is a mess, and it is so important that we have a media that actually can cover issues of war and peace.

RWM: When we were conceiving of Free Press and discussing it initially, the idea was it’s a long-term struggle to make this a political issue and actually organize enough people to effectively beat the corporate lobbies and build a media system that would serve the public interest. We thought of it as digging in for the long haul here. This is like the civil rights movement or the labor movement or the suffragette movement. It’s not gonna happen overnight.

We were thinking in terms of raising issues that weren’t even being considered to get them out in the open. But then this war is happening. And, as fate would have it, the Federal Communications Commission under Michael Powell — George W. Bush’s FCC — announces it’s planning to review all the remaining media-ownership rules for broadcasting with a clear eye to getting rid of them so that Rupert Murdoch and the same corporations that sold us this war with bullshit journalism would now be able to buy up whatever else remained.

That’s when Free Press suddenly found itself in front of a revolution out of nowhere. Suddenly, the media is a national issue. It’s getting a lot of attention from everyone. It forced us to become serious organizers right away; the training wheels were thrown off. We had to get right to work because people were looking at us to say, OK, what are you going to do now?

All of America is a news desert

CA: I’m interested in how you are seeing both the political opportunity that comes from the deep-seated distrust and outrage people are feeling today, which I think resonates with the kind of energy that we saw in 2003, albeit with a different flavor with Donald Trump in the mix and all that chaos. At the same time, you’re looking at this collapsing media landscape, where the big corporations still have huge power and influence. People don’t know what to do about this immense and shifting power and just how intertwined it is with their everyday lives.

JN: Craig, you’re getting at the heart of the matter. Our initial concept was that the media should be a political issue. That was a radical concept, right? To tell people that media itself should be a political issue, that you shouldn’t just see it as part of the infrastructure but, in fact, as something that we should all understand. If we weren’t involved, decisions about it were going to be made by a small corporate elite.

That was the core concept at the beginning. And we have yet to succeed, right? It’s a brutal struggle. There’s this ongoing struggle that I think Free Press has led the fight and done tremendous work to try and make this more of a reality. But we’re still a long way off from where we need to be.

Bob and I, back in 2000–2002, were already evolving toward this view that there was a very real chance that our media system wasn’t going to exist. By 2008, it was very clear that the whole thing was collapsing; it was falling apart. What I think people still struggle to understand is that we don’t have news deserts in America. We are a news desert — the whole thing.

Yes, we have elites who get their media from The New York Times and NPR. We have a lot of young people who get something off their phones, a video or something like that. But as for a media system that would actually underpin democracy in some sort of healthy way, it collapsed. And it collapsed on our watch. It wasn’t enough of a political issue as it was happening. The end result is we have ended up in a situation where information in America comes to people primarily through propaganda and through organized political advertising, which is propaganda, too.

We end up with this situation in America where our media system has collapsed as a realistic source of information needed in a democracy, especially at the local and state levels but even at the national level. At the same time, that void has been filled by charlatans and by people who have a goal not to inform the people but to make sure that people will do what they want.

The challenge now, and it’s a huge challenge, isn’t because we have become so divided as a country. You end up with people saying the media is horrible because it’s a left-wing media, or the media is horrible because it’s a right-wing media. And the reality is: The media is horrible.

Throwing the puck down to the other end of the ice

CA: What does the actual winning coalition look like when you squint and try to see it at this moment? How do we reach wider audiences with the potential and power to change things?

RWM: Unless you can give people a vision of something dramatically better, you’re not going to build a movement. Let the range of debate be defined by lobbyists in Washington, and you’re dead. At Free Press, the idea was that we have to get a public following that gets excited and understands the big stakes and isn’t just wedded to one lobby battling another lobby — King Kong vs. Godzilla. I think that’s still true.

You can build a mass movement when people start asking, yeah, why are we paying so much for this bullshit service? It’s because the companies own all the politicians. That’s where we want the fight to be. We can win that fight. We can go into any town hall in this country and win that debate. But as long as we’re debating gigabytes with AT&T versus some engineer from Verizon, people just go to sleep.

I think a political candidate should run saying internet access should be free. Set it up like the post office. It’s just there. No questions asked, and think of all the money you’ll save. Let’s debate something like that. Why do we allow these companies to have these monopolies? Why do we allow Facebook and Apple and Google to have these immense monopolies and make this incredible amount of money?

These are not peripheral issues. Media is at the absolute center of our political economy. But we need something that’s going to inspire people who aren’t investors, who don’t have another dog in the race, who aren’t lobbyists. That is not working. We’ve got to throw the puck down to the other end of the ice, as I like to say — their end of the ice, not the one where we are getting our butts kicked.

JN: The initial concept that Bob and I talked about — all those days when I’d ride my bike over to Bob’s house 25 years ago — was the only way we’re gonna get out of this is if people are marching on Washington, literally physically marching on Washington demanding something different. There were many things we didn’t know initially. But we did know that you couldn’t build a movement that was going to be effective if you didn’t have a mass understanding of the crisis. We’re a little nostalgic about 2003 because there was something of a mass understanding. A lot of people blamed the media very quickly for the war in Iraq and for the Patriot Act.

But the challenge today is that the internet wasn’t gonna create journalism. It wasn’t going to replace what it was killing. Bob and I are probably the least nostalgic people in the world for the old media system. We were critics of it.

But what has become clear is that the system — whoever’s in charge, whether it’s legacy media or whether it’s new media being created online — is going to kick journalism to the curb. Journalism is not going to be a part of this. It may exist as a boutique, where you can still go get The New York Times. But for the great mass of Americans, it is not there.

We have seen the deaths of newspapers across this country, magazines across this country, serious TV journalism, again and again and again. There’s been a culling of the ranks of journalists, so there just aren’t people practicing journalism at the level that there were. Our challenge today is to get people to understand that they need journalism, they desperately need it to know about what’s going on in their community, in their state, in their nation, in the world.

What I would suggest to you is that what exists in journalism today is driven much more than we understand by clicks and ratings. So it isn’t even journalism, right? It isn’t like, wow, here’s a big story. We got to go tell it even though maybe people aren’t gonna initially be interested because people have to know this. No, it is literally what remains of our journalistic infrastructure saying, yeah, I’m not sure if that’s going to get the clicks.

We’ve ended up in a situation that is incredibly dire. Despite the incredible work of Free Press and what it’s doing in New Jersey and other places, we don’t have that national sense that this crisis in journalism underpins a crisis of democracy. Until we get there, all of what we’re doing is going to be important but not transformational.

We don’t have a lot of time. We had more time decades ago. Now we have seen the possibility of a society where journalism barely exists, and where you might even elect political leaders that want to shut down or undermine what still exists. Journalism is in this urgent crisis moment. And yet, by and large, we always still find a way to talk about something else.

Reasons for hope

CA: Despite all of this, you guys are still optimists. What gives you hope that 20 years from now maybe we won’t be having the same conversation?

RWM: On the issues we’ve been talking about, the source of my optimism remains that in any group I meet with, there will be overwhelming support for making fundamental change. Recognition of the problem is deep-seated and it cuts across political perspectives. That’s a source of optimism.

If I went into a room and they said, no, I think we should pay more for cellphones, or I think journalism is too good, there’s too much good information, then I would say it’s hopeless. It would be a tougher fight if people saw the world that way. And I extend that more broadly to political organizing. On issue after issue, people tend to be pretty progressive. But they don’t have that opportunity to reflect that in our political culture and don’t see that reflected very often in our media culture.

JN: Bernie Sanders and I wrote a book called It’s OK to Be Angry About Capitalism — amazingly to us, it was a New York Times bestseller. Just saying it’s OK to be angry resonates with people. There are people who really are starting to look at structural challenges.

That gives me a great deal of hope because if we’re going to believe the market — and our friends on the right are always telling us we should put our faith in the market — well, the market seems to suggest that people actually want fundamental issues to be addressed. They want to look deeply at the structures that are failing us. And as they do that, there’s a much bigger opening to have a discussion about how media structures fail us and how they fail democracy.

Help Free Press keep fighting for the next 20 years: Donate today.

Check out the other posts in our 20th-anniversary blog series.