Happy Anniversary, Free Press!

Free Press Co-CEO Craig Aaron at a 2017 rally to save Net Neutrality

Maria Merkulova

Free Press turned 20 on Aug. 14, 2023 — marking two decades of our fight to transform our media system.

As this date approached, I thought a lot about the importance of sharing our history and telling our own story.

We know that when the history books are written, all too often the story ends up being what a public official said or how The Wall Street Journal framed an issue. The edges are dulled. The context is lost. The activists are erased. We lose the story of how change actually happened and who sparked it.

Leading up to the 20th-anniversary celebration we’re planning in Washington, D.C., for next spring, my colleagues and I are going to use this space to reclaim that history, revisit some of our biggest accomplishments — many of which are highlighted on this newly updated timeline — and tell the story of how Free Press has grown and changed over the past 20 years.

I first arrived at Free Press back in November 2004 — and never left. So this story is my story, too.

Opening the book

I was a few years out of college and working as an editor at In These Times magazine in Chicago when I came across a tiny book authored by Robert W. McChesney called Corporate Media and the Threat to Democracy.

Professor McChesney’s book, a miniaturized version of his masterpiece, Rich Media, Poor Democracy, argues that the media system we had wasn’t magical or inevitable — but the result of political and policy decisions that were being made in Washington backrooms in our names but without our consent.

For me as a young journalist trying to understand why it was so hard for independent and alternative voices to reach a wider audience, this was an incredibly powerful insight, one I didn’t learn in journalism school. At In These Times I had the opportunity to meet, befriend and edit McChesney and his longtime comrade and co-author John Nichols, a journalist at The Nation.

Back then I still saw myself as a journalist, not an advocate. But I was swept up by their simple but profound argument that the media wasn’t something that just happened to you — you could actually influence the media, reshape it and change it for the better.

To make that happen, though, you had to pay attention to the structures — and to the policies and politics that created them — and understand who was invested in maintaining or worsening the status quo.

Reading this little book was an eye-opening moment, when I found some answers I didn’t know I’d been looking for and started to believe another media system was possible.

I wasn’t alone.

Building Free Press: from idea to institution

McChesney and Nichols provided the spark; they saw the need for a movement to change the media. But they didn’t yet know how to build it.

In Northampton, Massachusetts, an activist named Josh Silver also read one of these books, and he called up McChesney to say he wanted to try and create that movement.

Silver was a persuasive advocate, fundraiser and pitchman who got people excited about creating a new group. Luckily for us, one of the people he pitched was Kimberly Longey, our self-described “orgitect,” who turned Free Press from an idea into an institution, one she still helps lead 20 years later.

Together, they assembled a small team in Western Massachusetts — including organizer Yolanda Hippensteele, web designer Ben Byrne and jill–of-all-trades Kate McKenney — and hired a McChesney graduate student and former Bernie Sanders staffer named Ben Scott to set up shop in D.C.

Free Press was omnivorous from the start: The first mediareform.net website was a barrage of links and issues. But the organization arrived at a moment when online activism was just emerging alongside a moment of deepening distrust in mainstream outlets.

Making the media the issue

The Free Press message that larger change was impossible without addressing the problems of the media coincided with the invasion of Iraq, after the media had furthered the lies that got us into that disastrous war. This was maybe the first time people began to really question what Fox News was and how it worked to manipulate viewers.

Massive giveaways during the 1990s from Congress and the Clinton administration — pushed by legions of corporate lobbyists — had killed local radio and replaced it with cookie-cutter playlists and Rush Limbaugh. The George W. Bush administration was trying to do the same for TV — all while refusing to even have a public meeting.

So we organized our own.

While then-FCC Chairman Michael Powell — a cable-lobbyist-in-training — stayed hidden in Washington, FCC Commissioners Jonathan Adelstein and Michael Copps went on tour, working with us to hold public hearings all over the country.

When I got to Free Press in 2004, my first assignment was to do press outreach for those hearings and chauffeur the commissioners around a bit. When I first saw 700 people lined up on a rainy Wednesday night in St. Paul to testify for five hours about what was wrong with the media, I knew we were on to something.

The NCMR era

In its first decade, Free Press put on a lot of big events — most notably six National Conferences for Media Reform, where thousands of people joined together for long weekends of panel discussions, performances and connections.

The conferences linked disparate strains of the media-reform and media-justice movements, old media and indymedia, artists and tech activists, the nascent blogosphere and Democracy Now! fans. So many notable media-makers and movement leaders took the stage at these events. Years later, I can still quote from the stem-winders delivered by Bill Moyers (“Democracy is two wolves and a lamb deciding what to have for dinner” — a Ben Franklin line he borrowed to call in our growing flock).

The best moments happened behind the scenes: There were groggy early-morning meetings, backstage acrobatics to keep the show going and late-night celebrations. We organized all the conferences in-house, and it was so much work. But deep trust and lasting bonds were forged in the chaos.

It’s also when we first discovered the talents of so many future Free Press leaders — like Candace Clement, Dutch Cosmian and Mary Alice Crim — who had joined Free Press as interns or receptionists but quickly became indispensable contributors to the broader movement.

Free Press alum Mary Alice Crim at the 2013 National Conference for Media Reform

Saving the internet

The biggest fight that Free Press found itself at the center of was Net Neutrality. While the “Save the Internet” campaign would mobilize millions over multiple flashpoints across more than a decade, it all started with maybe a half-dozen of us in a room sounding the alarm and realizing the bumbling telecom execs weren’t ready for us.

There have been so many highlights for the Free Press team: Tim Karr mocking the telecom companies when we won a Webby Award. That time Stevie Converse caught Comcast busing in people they’d paid to parrot company talking points at an FCC hearing in Boston. Pulling off the first major protest outside Google headquarters when it tried to cut a side deal with Verizon. When The Daily Show mentioned Net Neutrality for the first time. How excited we were when we got on the homepage of YouTube and The Huffington Post.

Or, my personal favorite, when the dance remix of Sen. Ted Stevens’ infamous “series of tubes” speech (“The Internet is not a truck … ”) went viral.

For years, Free Press lived on that grassy knoll up the street from the old FCC building, handing out breakfast (“Don’t Waffle on Net Neutrality”), herding cats (“Net Neutrality Is Purr-fect”) and leading so many chants into the megaphone.

Free Press’ Misty Perez Truedson with Free Press alum Jenn Topper

We lost. We came back. We were losing again. And then we won — big. I’ll never forget riding on the Metro when I got the call from the White House saying that President Obama was going to take our side and come out publicly for real Net Neutrality.

Fast forward to joining an actual standing ovation at an FCC meeting — which never happens. And sure it was for the commissioners, who finally did the right thing and voted to restore strong Net Neutrality rules. But it was really for us, for everyone who showed up to see the vote, even if they ended up in the overflow room.

Yeah, Trump ruined it. But we put up a hell of a fight. We showed what was possible. I think so often about Team Internet and the hundreds of protests we organized nationwide in 2017, culminating with that huge rally outside the FCC in 2017, the one with the big clock and Collette Watson singing to inspire the crowd.

Maria Merkulova

We didn’t win that day. But I still believe we will.

Flashes of brilliance

There are so many more moments I want to share but not enough space to do them justice: hula-hooping with Low Power FM activists outside the National Association of Broadcasters, setting up a giant billboard outside the FCC chairman’s dinner, rick-rolling a live FCC meeting, rewriting the “Humpty Dance” as a Net Neutrality-themed rap, protesting outside the headquarters of Comcast, Sinclair and Twitter.

Free Press Co-CEO Jessica J. González at a protest outside Twitter headquarters in 2019.

Brooke Anderson Photography

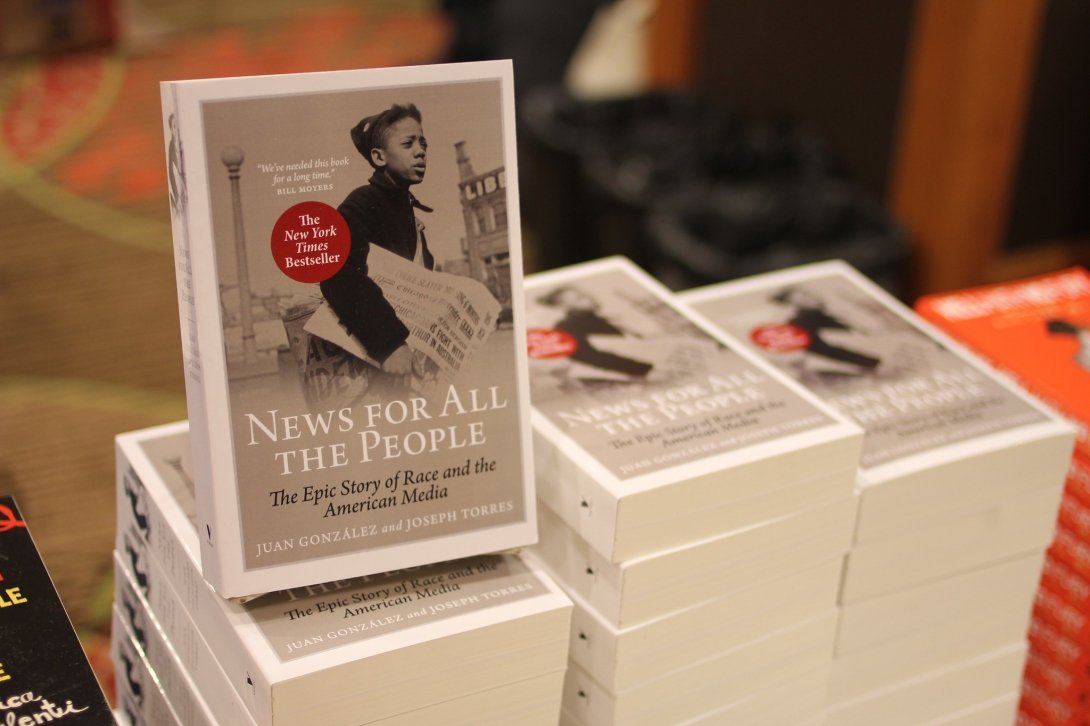

I remember seeing Joseph Torres’ News for All the People in a bookstore for the first time. Or that weekend we worked 36 hours straight to get Derek Turner’s book to the printer just in time for our policy summit. Watching Matt Wood testify before the Senate for the first time. Getting to stand with Mike Rispoli in a dingy hallway of the New Jersey statehouse to lobby for the Civic Info Bill.

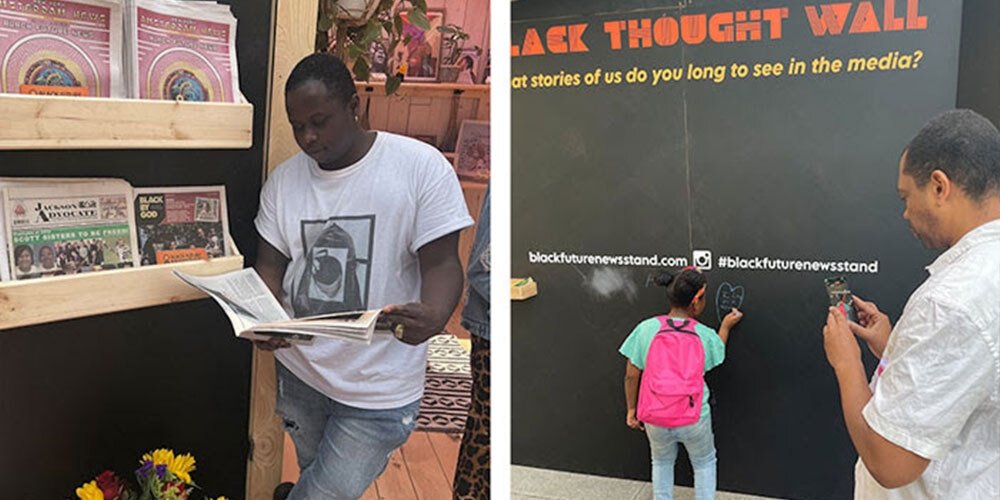

So many memories: hearing Alicia Bell ask a room full of uptight journalists to imagine “what the future smells like.” Seeing the response of students and young journalists when they watch the Black in the Newsroom documentary or share their reactions to reading the Media 2070 essay. Witnessing folks put their hands on the Black Future Newsstand.

When I tell the story of Free Press, it’s easy to make a long list of victories. Or if you’re me, a long list of favorite press hits and protest chants. (“Whose street? Sesame Street!” … maybe you had to be there.)

But the best parts aren’t actually found in the headlines and annual reports. They’re the shared moments at the back of the room, impromptu strategy sessions and late-night karaoke bonding. It’s the little dance I do in my living room when I hear we’re getting a big grant. It’s getting a call from Jessica González after Trump won in 2016 to say: “I know we’ve been talking about me joining the board of directors, but maybe you should hire me instead?”

The next journey

The full Free Press story — the more interesting if longer and nuanced one — is one of transformation. It’s a story of an organization willing to experiment, move and change. Maybe not always as fast as everyone would like, or maybe too fast for others. And, of course, not without mistakes. But with so many, many more successes.

So many incredible people — far too many to list — have come through here and helped shape and reshape this organization. They have gone on to become leaders in the government, political campaigns, the labor movement and the academy. (One of our interns even became a rock star.) Many of the best have stayed to keep building.

It’s no small accomplishment to have so many staff make this place their life’s work. Like many of the people name-checked above, there have been other staffers who have been here more than 10 years. I have to shout out Amy Martyn, Amy Kroin, Sara Longsmith and especially Misty Perez Truedson, who has done as much as anyone to shape the organization’s direction and build our culture.

It’s no secret Free Press didn’t start out as a racial-justice organization. The past 10 years of our journey — literally, since the day after our 10th-anniversary party — have been, in large part, about becoming one.

As recently as 2016, just 20 percent of the Free Press staff were people of color — now the majority are. In the early days, we were at arms-length with our allies of color; now they are our closest partners. That’s a transformation. And it’s part of what gets me so excited — even in the face of so many real-world challenges — about what the next 10 or 20 years will bring.

At Free Press, we are committed to transforming the media to realize a just society, to building an enduring multiracial democracy in this country, to being an organization that lives up to those values.

In the years ahead, we’ll be working to create new indelible moments, those sparks and flashpoints that awaken people — many, many more people — to new possibilities.

Media and technology aren’t just something that happen to us. We can reclaim, reform, reimagine and recreate them to improve our lives, represent all of us, help instead of harm.

More than ever, I believe in the ideas I first read in that little green book all those years ago: If you change the media, you can change the world.

I can’t wait to see what happens next.

Help Free Press keep fighting for the next 20 years: Donate today.

Check out the other posts in our 20th-anniversary blog series.