How Facebook Harms the Fight for Black Lives

This piece originally appeared in The Root.

Earlier this month, Baltimore County police tried to serve a Black mother with an arrest warrant for failing to appear in court for a traffic violation.

But the picture many saw told only one side of the story.

Police killed the woman, Korryn Gaines, and her 5-year-old son was wounded in the altercation. She had attempted to share her encounter with police using Instagram. The police urged Facebook, which owns Instagram, to deactivate her accounts.

In response, Facebook cut Gaines’ live stream from its feed.

Not an isolated incident

In July, Diamond Reynolds used Facebook Live to record the immediate aftermath of the horrific police shooting of her boyfriend, Philando Castile. Once footage hit 1 million views, Facebook temporarily removed the video.

A Facebook spokesperson claimed this was due to a “technical glitch,” but many media reports suggest otherwise.

For many, Facebook has come to represent a public square — a place where we can assemble with others, share information and speak our minds. But it isn’t public. It’s a private platform where everyone’s rights to connect and communicate are subject to Facebook’s often arbitrary terms and conditions.

The Constitution protects everyone’s right to record police officers in the public discharge of their duties. But this right goes only as far as your smartphone.

Once people decide to share the resulting videos — including those that expose shocking police abuses — the potential for state and private forces to censor the footage becomes very real.

Too much control over free speech

Facebook claims to take down or block videos that glorify violence and says that it will grant law-enforcement requests to suspend accounts in cases where there is an “immediate risk of harm,” but that’s a vague and difficult standard to apply, and one that’s subject to police discretion.

The Gaines and Reynolds videos remind us that social media companies like Facebook, Google (which owns YouTube) and Twitter ultimately control our ability to share the images that have fueled the Movement for Black Lives.

The fact that these companies can arbitrarily remove our speech, images and videos has serious consequences for those struggling to expose racial injustice to a wider audience.

Earlier this week, more than 40 social-justice and digital-rights groups sent Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg a letter (PDF) urging the company to clarify its policy on honoring police requests to censor videos and other content.

The groups, which include the Center for Media Justice, Color Of Change, Daily Kos, Free Press and SumOfUs, also asked Facebook to restore Gaines’ videos from her encounter with police so the public can decide whether the police violated her rights.

In the second half of 2015, Facebook received 855 requests from government and local authorities, including local police forces, for “emergency” action related to users’ accounts.

According to Facebook, these actions included the blocking of user access to accounts as well as the handover of user information. Over that time period, the company complied with nearly three out of every four such requests.

This raises several questions: Will police demand that Facebook cover up potential abuses that witnesses have recorded and then shared on the platform, even when there is no real risk of immediate harm? And how will it respond when the risk of harm comes from police violence itself?

Shouldn’t our right to record such interactions with law enforcement include our right to share these recordings with others?

Need for transparency

Facebook needs clear guidelines and processes that are transparent to users on how it determines whether to block someone’s stream or deactivate an account. It shouldn’t allow police to demand takedown requests to avoid scrutiny or cover up abuse.

We need to know when and why Facebook and other social media platforms have granted these requests, with clear standards for the future.

“Risk of harm” is a factor, but one could interpret that standard to justify censoring almost any interaction with law enforcement—and especially those in which an interaction escalates because of a person’s race.

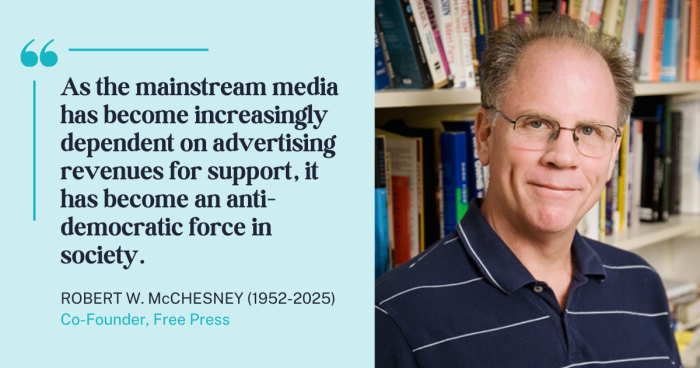

The fight for racial equity in the media is often a fight against media monopoly, especially when these companies are White-owned and operated. And Facebook is a face of monopoly in the age of social media.

New gatekeepers like Facebook must make confronting racism a priority. Yes, Zuckerberg has been outspoken in his support for racial justice — even hanging a Black Lives Matter sign outside company headquarters.

But we must urge him to ensure that his company’s actions match his words. Providing clarity and accountability on Facebook’s policy for suspending accounts and blocking images of police encounters is a start.