As Trump Lies, Here's How to Report on Civil Unrest

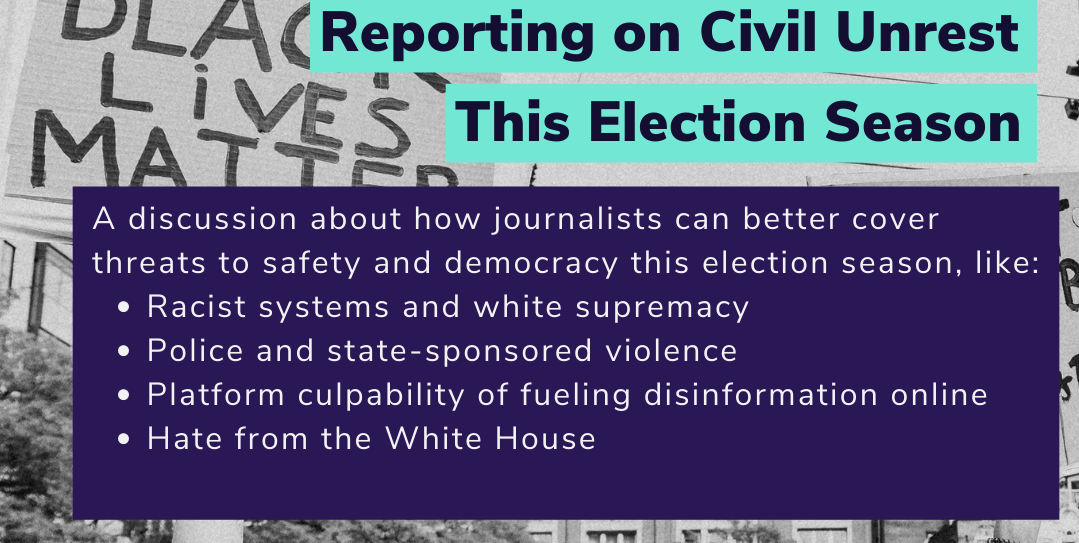

In October, Free Press organized the webinar “Reporting on Civil Unrest This Election Season” to give journalists a set of best practices for covering white supremacy and other forms of hate.

The conversation explored ways that reporters can curb hate on their own sites, deepen their understanding of systemic racism in media and tech and actively center and uplift impacted communities’ perspectives and expertise.

With Donald Trump protesting the outcome of the Nov. 3 election, these topics become even more relevant as we consider the potential implications of a president who refuses to accept reality — and is inciting millions of supporters to question the results and integrity of the democratic race.

Given that Trump has failed to commit to a peaceful transfer of power — and is now challenging the results by filing lawsuits and lashing out at reporters to undermine the public’s confidence — journalists must be on alert for any white-supremacist mobilization or organizing. Below are five tips journalists can use to ensure coverage of white supremacy and civil unrest is contextualized — and doesn’t amplify racist rhetoric or distort the impact racism has on Black and Brown communities.

This webinar, which I moderated, featured Al Letson, host of the Center for Investigative Reporting’s journalism show Reveal; Amity Paye, director of communications for Color Of Change; and Joan Donovan, research director of the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy.

1. All newsroom staffers, from executive editors to photographers to homepage producers and beyond, must acknowledge that America is rooted in white supremacy and racism.

By doing so, journalists, editors and newsroom leaders can ensure that coverage gives proper context and nuance about the conditions and factors in play that lead to civil unrest or public demonstrations that call attention to ongoing injustices.

“If you’re going to go out and report on these issues, you have to understand that the system in America is not broken; it’s functioning exactly the way it was intended to function,” said Letson. “If you understand from day one that it was built on white supremacy and everything that we have built in this country has grown out from that, especially when you’re talking about policing, when you’re talking about the court system, when you’re talking about housing, when you’re talking about education, every bit of that is tied to white supremacy.”

2. There are methods journalists can employ to connect white supremacy, racism and violence. This starts with centering impacted community members.

The first method is for journalists to acknowledge their bias, which can creep into their work and influence who they talk to, who they center their stories on and who they prioritize in their reporting. Bias can hinder journalists from reflecting on their own experiences, or lack thereof. Bias can also prevent reporters from linking violence and civic unrest to white supremacy and racism.

“[The] first thing to do is for reporters to really see themselves as they walk into a community and be able to see what biases or blind spots they may have and sort of sit with yourself and be honest, right?” said Paye. “Like what am I bringing into this story and into this reporting?

“I think that allows you then to say, ‘OK, I am afraid in a moment of protest because I’m out of my comfort zone. Here are the reasons why I understand that.’ And then you’re actually able to see other people for who they are and what is actually happening outside of your own experience. I feel like that’s a really big thing that I’ve said over and over to reporters.”

Letson agreed and added that reporters should think about prioritizing people’s lived experiences and struggles to gain more clarity.

“I remember thinking about this a lot in the Freddie Gray case in Baltimore, and [what] we saw [with] the uprising there is that this is a community that’s been without a voice for so long and they’ve banged on doors, they’ve done everything that America says that you’re supposed to do to get justice and justice never shows up. I just think that we’re all kind of trained to be like ‘oh my God, things are burning, that’s bad,’ when really we should be outraged at the way that people have had to live.

“You know, I think so much about [how] Black Lives Matter isn’t about the way we die, but it’s really about the way we have to live.”

3. There are ways to cover white supremacy and racism without giving white supremacists a platform. The methods involve adding context for clarity and being mindful of rhetoric and vernacular.

Donovan emphasized the need to point a spotlight on how social-media platforms are allowing hate, violence and racist rhetoric to thrive. She urged journalists to include information that carries a reader through these points to emphasize how racism festers and impacts their community and their safety.

“There’s been communities who have struggled to be heard for so long and I don’t know why journalists don’t have a repertoire for dealing with movements by now, where they don’t get caught up in outside-agitator narrative,” Donovan said.

That outside-agitator narrative, set by white supremacists, can lead journalists to identify a single individual or leader that is the cause of violence, but overlook the systems in place.

“White supremacists become this really important fulcrum for stories as the narrative driver. ‘If we could just get rid of these guys, we do not have to deal with any of the more systemic problems,’” Donovan said. “If these groups are organizing in your area, you have to call it as you see it. That might mean injecting a bit of analysis into your story rather than just saying ‘these are the five people that were on the block,’ especially as we start to look at vigilante groups.”

The language reporters use to describe people, groups and actions that are extensions of racism and white supremacy is extremely important, as it can legitimize a group or confuse the public.

“There’s been talk about not even calling these groups that are organizing these reopen protests as militias,” said Donovan, “because that gives them an air of legitimacy related to the Constitution. Of course [everyone] in America [knows] what it means to maintain a well-regulated militia … So it’s really important that journalists use specific terminology that is understood and then also think about the implications of just using terms that … carry with [them] a sense of valor and justification for those kinds of actions.

“If what white supremacists are doing in your city or town is illegal, you have to name it and call attention to it and try to get others in your area to take accountability for that.”

4. Be wary of how white supremacists use the media to build their base.

The media is a vehicle to influence thought, perspective and emotion and encourage people to address issues or concerns through civil, political and sometimes physical means. Journalists should be wary of giving white-supremacist groups space or time to express their beliefs and gain exposure, notoriety or credibility. Always think about the intentions or reasoning that white supremacists and hate groups are using to engage with you or your colleagues.

“White-supremacist groups, if you’re thinking of the Proud Boys, they actually use the media to grow their ranks” said Paye. “So I think as folks are reporting, you should really see yourself as … potentially a tool for white-supremacist groups to do recruiting. They have specifically said that they use reporters and the press to do that. And so I think reporting on these stories is not neutral in any way, particularly because they know how the press works.”

5. Engaging with activists can lead to stronger storytelling and impact.

Often journalists view activists as people with agendas — instead of as community members who are trying to address issues that impact them or a community they care about. This othering can bury important stories that speak to the media’s crucial function as a watchdog against those in power.

“[See] activists as almost a door to understanding the issues of a community … those are folks that are taking a stand, but they also know everyone. They’re the people that can find you the best stories. It’s deeper storytelling and really shares information with people on a more activating level,” said Paye, who mentioned that Pulitzer Prize-winning journalists are sometimes the ones who stick with a community long enough by engaging with activists, learning about their networks and really integrating with residents.

And how can journalists get to that deeper level of storytelling? Talking with activists first.

“Start with the activists. You get to know them, get to know the issues that they are fighting for, why they’re fighting, who they’re fighting with. What you do is you start to get to know the people that are directly impacted by what’s going on on the ground,” said Paye.

Following this webinar, Free Press’ News Voices team created a database of more than 100 resources and guides to help journalists keep communities informed and safe before, during and after the election.

You can access the database here and contribute to our growing resource list.

And watch the webinar below.