How Local Media Fueled the Tulsa Massacre — and Covered It Up

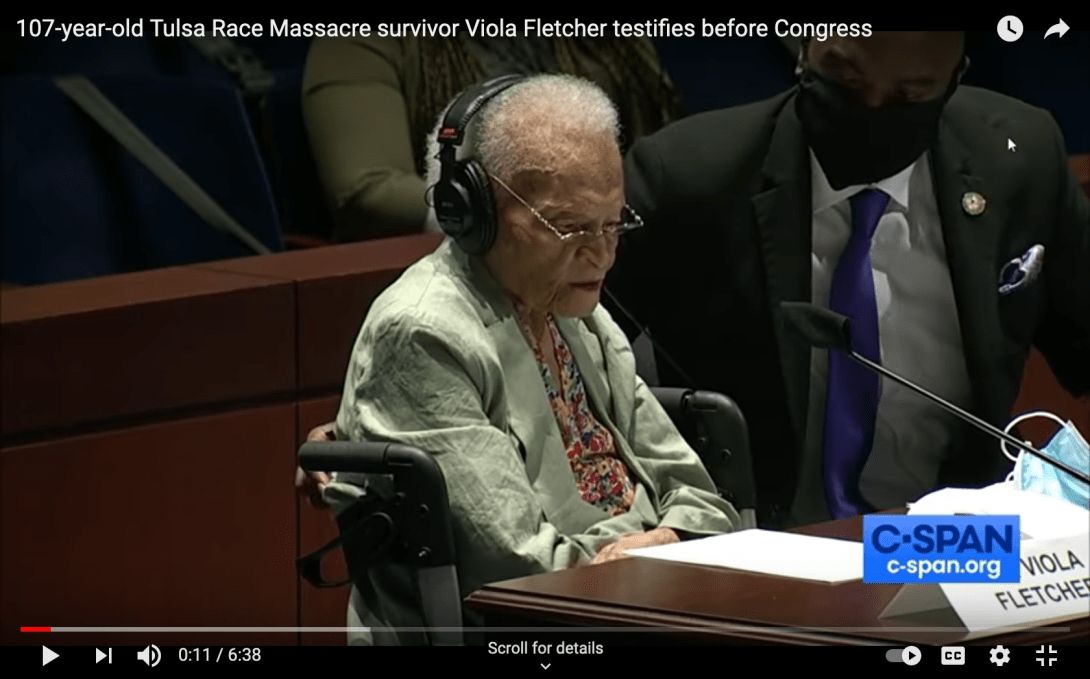

Viola Ford Fletcher, a 107-year-old survivor of the Tulsa Massacre, testified in Congress about the devastation and trauma she and her community experienced.

The upcoming commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Massacre is a reminder of the critical need for our nation to acknowledge its history of anti-Black racism and violence.

The Tulsa massacre is considered one of the deadliest acts of racial violence committed against the Black community in our country. Until recent years, few people had heard of it. The city’s political power structure refused to acknowledge what happened, betting that memories of the massacre would remain buried in the past.

But Black Tulsans and allies forced the city to reckon with its history and to acknowledge the massacre that began on May 31, 1921, when thousands of white residents invaded the thriving Black community of Greenwood — known as “Black Wall Street” — and slaughtered its citizens. The massacre lasted 18 hours. And even though the true death toll remains unknown, an estimated 300 people were killed. The majority were Black.

This year’s historic anniversary arrives as our country is in the midst of a racial reckoning. Following the public execution of George Floyd last year, the Black community has pressured our nation’s public and private institutions to acknowledge their own histories of anti-Black racism. This reckoning has included many influential media outlets.

Over the past year, The Los Angeles Times and The Kansas City Star have apologized for their racist histories. And as Tulsa observes the 100th anniversary of the massacre, it’s crucial that we remember the role the city’s newspapers played in weaponizing anti-Black narratives. Tulsa’s newspapers did this to further the political goals of white supremacy and protect a white-racial hierarchy — a hierarchy that these news outlets were part of.

These newspapers played a major role in the massacre and its cover-up. And the results were devastating.

Tulsa’s racist dailies

In 1921, Tulsa had two daily newspapers — the Tulsa World, a morning publication, was founded in 1905. Richard Lloyd Jones purchased a rival afternoon paper in 1919 and renamed it The Tulsa Tribune.

Author Tim Madigan describes Jones as the city’s “most vocal racist.” And his newspaper coverage often reflected his racist views. Madigan notes that for months prior to the massacre, the Tribune published on its front page what was essentially a public-relations ad for the Ku Klux Klan: Accompanied by a prominently placed picture, this “article” discussed the Klan’s expansion plans for Oklahoma. In his book about the massacre, Madigan writes:

“Jones’ paper published what amounted to a press release for the new KKK, a story that lauded the secret order’s ambitions to add chapters in Oklahoma. The new Klan, the story said, was to be a living lasting memorial to the original Klan members who had saved the South from a ‘Negro empire built upon the ruins of southern homes and institutions.’ Among the KKK’s principles, the Tribune article continued, was ‘supremacy of the white race in social, political and governmental affairs of the nation.’”

Author James S. Hirsch writes in his own book about the massacre that Jones’ editorials often “revealed his xenophobic and white supremacist attitudes.” Jones opposed the admission of Hawaii as a state because, in his view, it had too many “orientals.” He criticized the United States for helping “incompetent people” in countries like India, China and Japan and said that he “believed in the noble-minded men working in the KKK.”

And as Hirsch notes, Jones once even had the KKK guard his home due to a “bomb scare.”

Both the Tribune and the World ignored the lives of Black Tulsans in their news coverage aside from stories that portrayed the community as criminals. But according to the Tulsa Race Riot Commission’s 2001 report, the Tribune’s crime coverage shifted its primary focus to Black criminality 10 days prior to the start of the massacre. The Commission wrote:

“In a lengthy, front-page article concerning the on-going investigation of the police department, not only did racial issues suddenly come to the foreground, but more importantly, they did so in a manner that featured the highly explosive subject of relations between black men and white women. Commenting on the city’s rampant prostitution industry, a former judge flatly told the investigators that black men were at the root of the problem. ‘We’ve got to get to the hotels,’ he said, ‘We’ve got to kick out the Negro pimps if we want to stop this vice.’”

On the afternoon of May 31, the Tribune published a front-page story with the incendiary headline “NAB NEGRO FOR ATTACKING GIRL IN ELEVATOR.” The five-paragraph piece provided sensational details about the arrest of Dick Rowland, a 19-year-old shoeshiner who was falsely accused of sexually assaulting a 17-year-old white girl. Following the massacre, the charges were dropped.

Tulsa lawyer B.C. Franklin, the father of the legendary historian John Hope Franklin, recalled hearing high-pitch sound of a newsboy yelling — “A Negro assaults a white girl.” And according to witnesses and survivors of the massacre, the Tribune also published an editorial with the headline “To Lynch Negro Tonight.”

There’s a long history of newspapers using the racist trope of Black men preying on white women to advance the political goals of white supremacy — and this coverage fueled state-sanctioned extrajudicial lynchings.

The Tribune’s sensational coverage acted as an accelerant that mobilized about 2,000 white residents to gather at the jailhouse later that evening and demand that the police hand over Rowland. But Black Tulsans, including World War I veterans, showed up at the courthouse armed and offered their services to the police to help prevent Rowland from being lynched. The police, however, twice declined their offer.

The Race Riot Commission found that “Black Tulsans had every reason to believe that Dick Rowland would be lynched after his arrest on charges [that were] later dismissed and [were] highly suspect from the start.” The commission noted that Black residents “had cause to believe that [Rowland’s] personal safety, like the defense of themselves and their community, depended on them alone.”

A scuffle ensued outside the courthouse when a white Tulsan tried to take a gun from an armed Black citizen. A shot was fired. The massacre began.

Soon, the police deputized white men, providing them with weapons and ammunition. Thousands of White Tulsans invaded the Greenwood District, which they commonly referred to as “Little Africa,” and started murdering Black residents — including women and children — indiscriminately.

The Race Riot Commission reported incidents where members of the local police and National Guardsmen took part in the violence and noted that airplanes flew above Greenwood, with men firing at Black Greenwood residents below. The commission also said that evidence indicates that at least one plane dropped explosives — likely dynamite — on the Greenwood community. Many armed Greenwood residents fought back. But they were outnumbered.

When the massacre ended, Black Tulsans made up the vast majority of an estimated 300 people who were killed. White invaders had burned down the Greenwood district, destroying more than 1,200 homes and leaving an estimated 10,000 Black Tulsans homeless.

In addition, Black-owned businesses and institutions were destroyed, including 12 churches, five hotels, 31 restaurants, four drugstores, eight doctors’ offices and two-dozen grocery stores. And the National Guard rounded up 6,000 Black citizens and placed them in concentration camps.

The offices of the city’s two Black-owned newspapers — The Tulsa Star and Oklahoma Sun — were also destroyed.

The Star’s publisher — A.J. Smitherman — was a prominent Black leader in Tulsa whose newspaper covered the community extensively, with articles on everything from politics to graduation ceremonies and wedding announcements. But now, the voices of these two critical Black journalism institutions were silenced. Press freedom — like so many other so-called fundamental democratic rights — has often not applied to the Black community.

Black Tulsans blamed

Initially, newspapers across the country, like The New York Times, published front-page stories about the massacre. Several newspapers, like The Houston Post, The Kansas City Journal and The Nashville Tennessean, condemned what happened.

But in Tulsa, the city’s politicians and the white-owned daily newspapers blamed the Black community for the massacre and framed it as a Negro uprising against the white community. Smitherman, the Tulsa Star publisher, fled the state after false charges were brought against him and other prominent Black residents for causing the riot.

The Tulsa World reported that Tulsa Mayor T.D. Evans said that Black people people were to blame for the massacre, which he described as “inevitable.” He argued that it was good that the destruction of Greenwood happened:

“Let the blame for this negro uprising lie right where it belongs - on those armed negroes and their followers who started this trouble and who instigated it and any persons who seek to put half the blame on the white people are wrong and should be told so in no uncertain language. … It is the judgment of many wise heads in Tulsa, based upon observation of a number of years, that this uprising was inevitable. If that be true and this judgment had to come upon us, then I say it was good generalship to let the destruction come to that section where the trouble was hatched up, put in motion and where it had its inception.”

Meanwhile, Tulsa World also blamed the massacre on the Black community in its June 4th editorial “Bad Niggers”:

“There are those of the colored race who boast of being “bad niggers.” These it was, seizing the merest semblance of an excuse, who armed themselves and invading the business district of the city defiantly sought to take the law into their hands. If possible harmony between the races is to be restored in Tulsa these ‘bad niggers’ must be controlled by their own kind.

“The innocent, hard-working colored element of Tulsa faces both a danger and an unescapable duty if the work of those who seek to restore and tranquilize is to accomplish anything. They must co-operate fully and with vast enthusiasm with the officers of the city and county in ridding the community of worthless, boasting, criminal ‘bad nigger.’”

In the same editorial, the paper also called on Black Tulsans to protect themselves against “worthless Negroes”:

“The time is here for the colored citizens of the city, who work for their living and render a substantial service to the community, to band themselves together for their own protection against this element of non-working, worthless Negroes.”

The editorial also warned the Black community to reject leaders who fought for “equality” since it would never be realized:

“School yourselves to a becoming attitude in your associations. Exert yourselves to bring to justice criminals and law violators of your own color. Be respectful. You have leaders of your own race who are safe and sane. Hear them. Avoid the boastful intriguers who prate to you of race equality. There has never been such a thing in the history of the world. Nor will there ever be.”

In the World’s June 5 editorial “In Work There is Salvation,” the paper supported the mayor’s cruel threat to arrest Tulsans who were not cleaning up the destruction caused by the massacre — a threat that clearly targeted the city’s Black residents. The World called for Black residents to be “scourged” if they didn’t cooperate:

“The worthless shiftless Blacks who refuse to work should be made to work. The apparent tendency on the part of some of them to sit back in ease because of decent efforts of the citizenship to undo that which has been done, should and must be met with an iron hand.

“Tulsa wants no shiftless, idle class, either white or black. The time has come when our Augean stables must be cleaned. And in the cleaning no color line should or can, in common justice, be observed. The shiftless, criminal element must be either reformed or driven from the city. Tulsa must be purged.

“The splendid citizenship of the city is contributing of its substance for a cause considered worthy … And if men of color seek to take advantage of the splendid outburst of sympathy instead of co-operating with it and proving their worthiness of it, they should be scourged.

“Tulsa as it is functioning now is not demonstrating in behalf of worthless, silk-shirted and impudent colored men, but demonstrating in behalf of innocent women and children and hard-working colored people who it is fondly believed gave no offense and contemplate no offense.”

Meanwhile, The Tulsa Tribune advocated against the rebuilding of Greenwood in a June 4 editorial — “It Must Not Be Again” — and blamed “bad niggers” for starting the riot:

“Such a district as the old ‘Niggertown’ must never be allowed in Tulsa again. It was a cesspool of iniquity and corruption. … In this old ‘Niggertown’ were a lot of bad niggers and a bad nigger is about the lowest thing that walks on two feet. Give a bad nigger his booze and his dope and a gun and he thinks he can shoot up the world. And all these things were to be found in ‘Niggertown’ - booze, dope, bad niggers and guns.”

The editorial also blamed the police commissioner for failing to deal with the growing agitation in “Niggertown”:

“Well, the bad niggers started it. The public would now like to know: why wasn’t it prevented? Why were these niggers not made to feel the force of the law and made to respect the law? Why were not the violators of the law in ‘Niggertown’ arrested? Why were they allowed to go on in many ways defying the law? Why?”

In its June 5 editorial, the Tribune called for building back a city that was “nobler.” The piece used racist epithets and the historical racist framing of Black criminality to claim that Black residents had plotted a violent attack on the white community:

“There most of the criminal of the community both white and black found harbor. There crimes were plotted. There an uprising has long been in process of planning. There this disorder begun. The bad elements among the negroes, long plotting and planning and collecting guns and ammunition, brought this upon Tulsa just as the winds gather into a cyclone and sweep upon a city. This bad element among the negroes must learn this is not a city of, for and by their kind. NEVER.”

The editorial concluded by stating that Tulsa was going to lift “her head from her hour of shame with a firm resolve to clean house” as it rebuilt:

“What is more, the public spirited, prideful citizens of Tulsa have met in conference to resolve and lay plans to rebuild and restore that which the lawless have destroyed and to build a cleaner, a better and a more sanitary section of the city than that which ends in ashes.

“Tulsa will redeem her splendid name before the world. The Argonaut days of Tulsa are history. The finer city with a nobler and truer spirit and an awakened conscience is the aftermath of this disaster.”

No one was ever held responsible for the murders committed during the massacre or for the destruction of Greenwood. Instead, public and private institutions in Tulsa tried to erase the massacre from public consciousness. The Tribune didn’t even mention the massacre in its paper until 1971.

“The bottom line is that for half a century, the white newspapers of Tulsa intentionally kept the massacre buried,” said author and historian Scott Ellsworth, whose books and other writings have played a critical role in ensuring that Tulsa reckons with its history.

In fact, the microfilm for The Tulsa Tribune’s May 31, 1921 issue is missing both the news story about Rowland’s arrest with the headline “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator” and the editorial that predicted a lynching that evening. Both the article and editorial were intentionally removed. But in 1946, a college student working on a thesis about the massacre found a copy of Rowland’s arrest article. The editorial, however, remains missing.

In his book, Madigan writes that the editorial had appeared in the paper’s initial run — but Tribune staffers convinced Jones to remove it from additional editions that were printed that day and attempted to remove copies of the paper featuring the editorial predicting a lynching that night.

The Tulsa Race Riot Commission discussed the missing editorial in its 2001 report:

“Given the fact that the editorial page from the May 31, Tulsa Tribune was also deliberately removed, and that a copy has not yet surfaced, it is not difficult to conclude that whatever else the paper had to say about the alleged incident, and what should be done in response to it, would have appeared in an editorial.”

The World and The Tribune entered into a joint operating agreement in 1941 and shared business operations until the Tribune ceased operations in 1992. The World remains Tulsa’s daily newspaper.

Reckoning with its history

While Tulsa’s politicians and institutions tried to erase the memories of the Tulsa massacre from the city’s collective memory, many Black activists, journalists, leaders, survivors and their descendants worked to ensure that the carnage was never forgotten.

Teacher and journalist Mary E. Jones Parrish lived in the Greenwood District. And during the massacre, she and her daughter fled for their lives. In 1922, Parrish published the book Events of the Tulsa Disaster, which provided firsthand accounts, including her own, of what happened during the massacre. The Tulsa Race Riot Commission noted:

“Parrish interviewed several eyewitnesses and transcribed the testimonials of survivors. She also wrote an account of her own harrowing experiences during the riot and, together with photographs of the devastation and a partial roster of property losses in the African American community, Parrish published all of the above in a book called Events of the Tulsa Disaster. And while only a handful of copies appear to have been printed, Parrish’s volume was not only the first book published about the riot, and a pioneering work of journalism by an African American woman, but remains, to this day, an invaluable contemporary account.”

In 1971, dozens of survivors took part in a small commemorative ceremony at Mount Zion Baptist Church. As the commission noted, the “event represented the first public acknowledgment” of the massacre in decades.

That same year, the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce asked Ed Wheeler, a white man and host of a local radio program, to write an article about the massacre for its magazine. But white men — strangers — subsequently approached Wheeler and warned him not to write the article. In addition, someone used soap to write a message on his car windshield that read: “best check under your hood from now on.” But Wheeler kept on.

The Tulsa Chamber of Commerce, however, decided not to publish his article and two Tulsa dailies also declined. Hirsch’s book notes that an editor at the World called the story “wonderful” but told Wheeler the paper “[wouldn’t] touch it with an eleven-foot pole.” Instead, Impact, a Black-owned magazine, published the article. It was edited by Don Ross, a legendary figure in Oklahoma history.

Ross began his journalism career during the early 1960s as a columnist for the Oklahoma Eagle, a Black newspaper that had been owned by the Goodwin family since 1936. He wrote three columns about the massacre for the Eagle in 1968 and a column for Impact on the 50th anniversary of the massacre. In 1982, Ross was elected to the Oklahoma House of Representatives and in 1997, he wrote the legislation that led to the creation of the Tulsa Race Riot Commission, which published the report discussed here and recommended reparations for the survivors of the massacre.

The Oklahoma Eagle played a critical role in Ross’ career and has served as a voice for Black Tulsan residents since its founding. After a white mob destroyed The Tulsa Star during the massacre, the publisher of the Sun — whose paper was also destroyed — salvaged The Star’s printing presses and launched the Eagle in 1922. In 1936, E.L. Goodwin became the owner of the Eagle. His father had once worked at the Star and his son, James, is still the publisher of the Eagle.

A 2020 Los Angeles Times profile of the paper noted that “every Thursday for decades — through editorials, news stories and photos — the Eagle has forced the city to confront its violent past.” The paper also publishes editorials every year on the massacre’s anniversary “calling on lawmakers to remember” what happened.

The creation of the Tulsa Race Riot Commission and the publication of its 2001 report generated significant coverage of the massacre. A number of books and documentaries have since been published and produced. Many people also learned about the massacre for the first time from the popular HBO series Watchmen. And greater media attention is being paid as the 100th anniversary approaches in the midst of a racial reckoning.

But while the Black community continues to fight for justice and reparations, the story of what happened in Tulsa remains a threat to our nation’s white-racial hierarchy. The right wing has adopted the framing of “cancel culture” as a strategy to prevent accountability, including addressing our nation’s history of anti-Black racism and the harms inflicted on the Black community.

Just this month, Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt signed a law that prohibits the teaching of critical race theory, a framework that examines how laws shaped by racism have impacted communities of color. The new law is part of a right-wing campaign to prevent our nation from learning about the history of systemic racism and state-sanctioned violence against the Black community — such as what happened in Tulsa a century ago.

But this resistance to acknowledging and redressing the history of anti-Black racism is a reason why the three known survivors of the Tulsa massacre — Viola Ford Fletcher (107), Lessie Benningfield Randle (106) and Hughes Van Ellis (100) — testified before Congress about the need for reparations. Fletcher and Van Ellis testified in person despite the pandemic.

The three survivors and descendants of survivors filed a lawsuit last year against the city and the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce for their role in covering up the massacre and blaming the Black community for the violence.

Fletcher, whose appearance at the hearing marked her first time in Washington, D.C, said during her testimony that she was asking her “country to acknowledge” the massacre. “Our country may forget this history,” Fletcher said. “I will not. The other survivors do not. And our descendants do not.”

She concluded her marks by stating:

“We lost everything that day. Our homes. Our churches. Our newspapers. Our theaters. Our lives. Greenwood represented the best of what was possible for Black people in America – and for all people. No one cared about us for almost 100 years. We, and our history, have been forgotten, washed away. This Congress must recognize us, and our history. For Black Americans. For white Americans. For all Americans. That’s some justice.”