Plan Fail: How Pai Imperiled a Rural Town's Fiber Network

Original image by Flickr user Verkeorg

Note: This is part five in an ongoing series. Be sure to check out the previous posts:

Part 1: Fiber to the Clubhouse: Pai Subsidizes Broadband for the Rich

Part 2: Broadband Boondoggle: Ajit Pai’s $886M Gift to Elon Musk

Part 3: Space-X Broadband: Coming to an Empty Traffic Island Near You

Part 4: Ajit Pai’s Broadband Legacy: Haste and Waste

Part 6: Good News: Mass. Muni Fiber Spared from FCC RDOF Blunder

Part 7: Why Elon Musk Is No Longer Getting $886M from the FCC

Free Press co-founder and COO Kimberly Longey is someone you want to have on your side.

She helped build our organization from an idea on paper to the force it is today — and that’s just her day job. In her spare time, she organized a municipal project to bring fiber internet to her town of Plainfield, Massachusetts, finally giving the people in this community much-needed high-speed connectivity after years of frustration with Verizon.

Turning a wish and a need into a reality required a substantial amount of work beyond even the endless hours spent in meetings. Building a fiber network requires accurate knowledge of where all of the potential customer locations are, and getting enough of those people to sign up.

Longey and a team of local volunteers literally drove all of the roads and backroads in her town to map the area and understand their potential customer base — a necessary step that many winners of subsidies from the FCC’s Rural Digital Opportunity Fund (RDOF) obviously didn’t take, judging by the myriad of questionable awards documented in our prior posts.

Longey’s muni-broadband provider — Plainfield Broadband — built its infrastructure in partnership with a utility company in the area, Westfield Gas & Electric (or “G&E” for short). The project broke ground in July 2019 and now offers service to all of Plainfield.

The total network-construction costs were approximately $2.3 million, and were paid for using $1.5 million in funds raised and appropriated by Plainfield voters, with the remainder coming from the Last Mile Infrastructure Grant program administered by the Massachusetts Executive Office of Housing and Economic Development. Plainfield is among 21 towns in Western Massachusetts that are working with Westfield G&E to design, construct and operate their publicly owned networks.

On Feb. 13, 2020, the FCC granted final approval to Westfield G&E to receive subsidies from the Connect America Fund Phase II (“CAF II”), which it had won in a reverse auction that commenced in July 2018. Of the $10.3 million awarded to Westfield G&E, Plainfield broadband will receive subsidies totaling $430,686 over a 10-year period, which will be used to pay down the debt the town’s residents took on to build the network.

But less than a year after the FCC approved $10.3 million of CAF II Universal Service Funds to help pay for the cost to build Plainfield Broadband and municipal-fiber systems in 20 other towns in the region, the agency awarded $9.4 million of RDOF subsidies to Charter to overbuild these taxpayer-funded networks. While in most areas it certainly makes sense to have as many providers as possible, this is not the case in areas that are by definition uneconomical for even one provider to serve without subsidies.

Indeed, that’s the entire point of the FCC’s universal service “High Cost” fund: to ensure telecommunications services are available at reasonable prices in areas where there’s no business case for a private provider to serve without some subsidy.

It’s just bad policy for the FCC to subsidize multiple fiber networks in a single rural area. It’s especially terrible for the agency to fund a giant ISP like Charter to come in only after the residents of these tiny towns went out of pocket to build their own networks (the 20 other area municipalities also partnered with Westfield G&E and received CAF II awards).

While many public-interest advocates understandably say that overbuilding should be allowed and even encouraged in the market for broadband, subsidizing multiple providers is a different question altogether — especially when it involves subsidizing a cable-company behemoth to overbuild a hard-won local option.

So why is the FCC subsidizing Charter to overbuild in Plainfield and other rural Massachusetts towns that are already or will soon be served by other agency-subsidized ISPs? As we show below, it’s because of former FCC Chairman Ajit Pai’s mismanagement. Pai never missed a chance to pat himself on the back for things he didn’t actually accomplish — and he failed to get the details right in this essential FCC program.

The FCC is giving Charter money to deploy gigabit networks in rural areas where it already subsidizes voter-approved municipal providers that deployed fiber service after years of effort by the towns and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts

In this post, we take a close look at how the FCC’s RDOF funded Charter to overbuild the municipal broadband network in Plainfield. But Plainfield’s story — and the threat the Pai FCC’s bungling poses to its municipal-fiber project — is not unique.

Unlike the suburban examples closer to the Westfield, Massachusetts airport described in our prior post, Plainfield is a truly rural area. All 92 of its census blocks are classified as such according to the Census Bureau’s definition. So it might have stood to reason that these actually were unserved, high-cost areas. But let’s look closer.

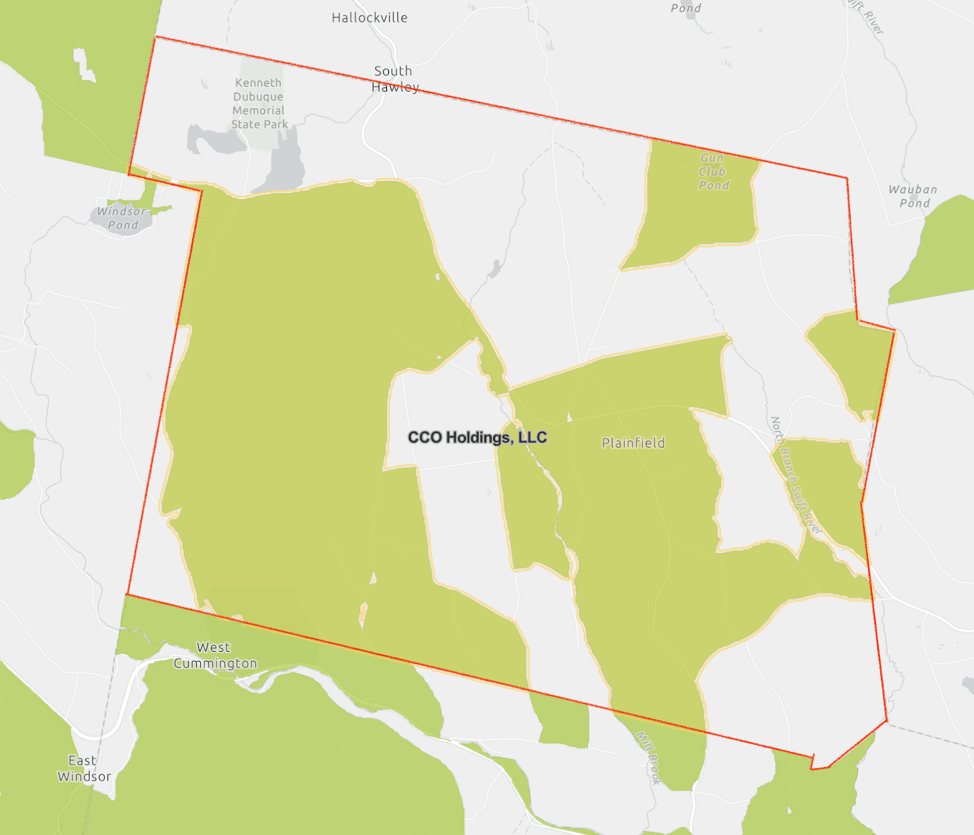

The map below shows the portions of the Plainfield census-block group for which Charter won a $555,840 RDOF award to deploy gigabit-internet-access service. Plainfield’s borders are outlined in red; Charter’s RDOF area is shaded green, and denoted using the name “CCO,” which is a Charter holding company.

Cooperative Network Services, LLC

The Charter RDOF award for Plainfield consists of 28 individual census blocks within the larger 92-block group covering all of Plainfield. According to FCC estimates, there are 700 people residing in 296 households in Plainfield. The 28 Charter RDOF blocks contain 410 of those people living in 179 total households. The FCC estimates that there are 244 serviceable customer locations (counting households and businesses) in these 28 census blocks.

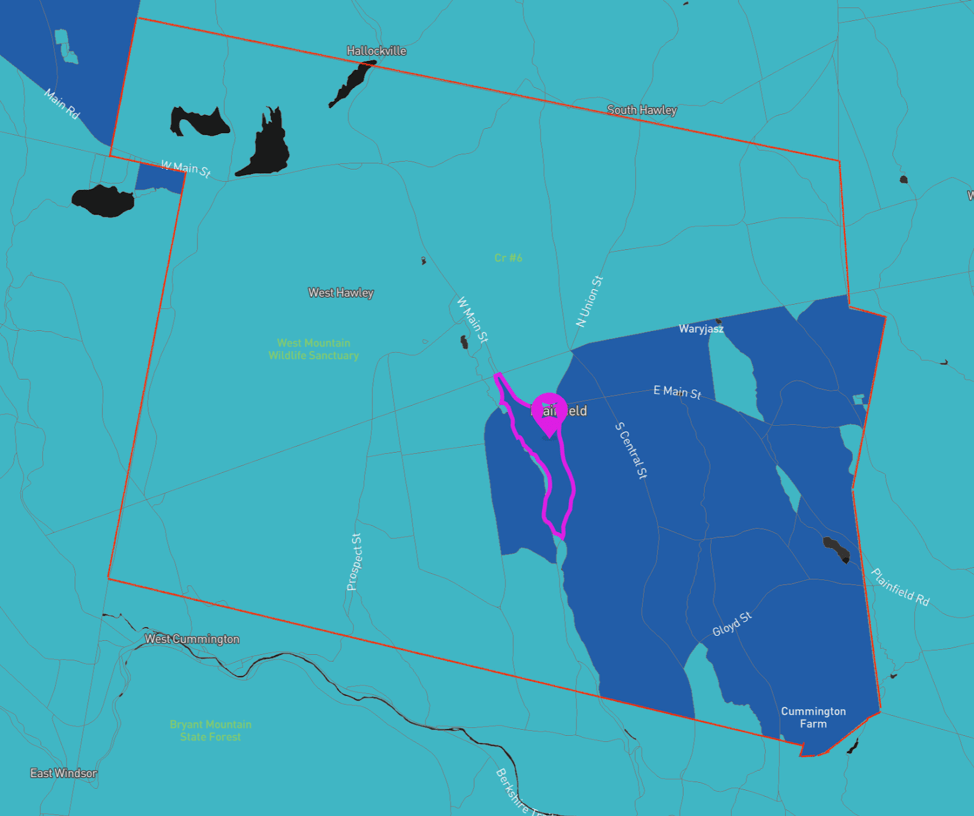

Now here’s the most-recent FCC Form 477 data for Plainfield, which reflects deployment as of year-end 2019, when the Plainfield fiber project was still in the midst of construction.

As we can see, some of the blocks where Charter won RDOF funds were already served with fiber by the end of 2019, or are adjacent to those already-served blocks.

But the key point is that whatever the status was at the end of 2019, as of the end of 2020 the entire town of Plainfield — every single customer location in every single block — was served by Plainfield Broadband. Per the FCC’s definition, that means service is already in use or could be provisioned within 10 days. The FCC rightly doesn’t require that every single customer subscribe for the home to count as “served” and covered, nor does it require the ISP to connect in advance a non-subscribing home that it could serve within that 10-day timeframe.

Plainfield Broadband indicates its service “passes” every single potential customer location in the town, with fiber running along all of the roads and to the town’s borders. Eighty-two percent of the town’s occupied potential customer locations are already current customers of Plainfield Broadband, or have received a “fiber drop” connection from the street to the outside of the customer premise. (The remaining 18 percent, as Longey reports, have not yet responded to the local team’s multiple outreach and marketing efforts, but they would be served if they requested service.)

Robots run amok

So why did the FCC award Charter RDOF subsidies to build in Plainfield when months earlier it gave Westfield G&E CAF II subsidies to support Plainfield’s own fiber network there? The FCC’s RDOF rules prohibit duplicative support — so did the FCC violate its own rules?

The answer is no. The 28 RDOF-funded Charter blocks do not overlap with the 30 CAF II-funded blocks. But this raises more questions, and highlights the inherent problem in the FCC’s and major bidders’ apparently “robot-driven” approach to rural broadband deployment.

The autopilot nature of the results here is apparent on both the ISPs’ side and the agency’s. As our previous post shows, Charter doesn’t even offer service in the large swaths of Western Massachusetts we’re examining. Comcast does in some of them — as do Verizon and now Westfield G&E, but Comcast is the key comparison point.

It would be great for internet users if legacy cable operators like Charter and Comcast really did jump into each other’s service territories and compete with each other, but they just don’t do that. And it doesn’t matter whether that’s because these companies have unspoken agreements, of dubious legality under antitrust laws, to divide markets geographically, or whether it’s just dictated by the economics in their view.

What matters is that Charter suddenly showing up to fill in some holes in Comcast country — or even to encroach on Comcast’s turf in areas that Comcast itself likewise declines to serve — is completely out of the ordinary.

It all leads us to question whether Charter really intended to build in this area, which is wholly disconnected from the company’s existing service territory and networks — or whether something strange is going on, and there’s a business planning switch-up or communications breakdown inside the company. We just don’t know.

But the robots also ran amok at the FCC.

It appears that the 28 RDOF-eligible blocks were not eligible for the CAF II auction because these blocks were considered “served” due to Verizon offering DSL at the 10 megabits per second (Mbps) level as of 2018. Because this partial Verizon DSL deployment met CAF II’s slower minimum-speed threshold of 10 Mbps for determining whether an area was served, Westfield G&E’s CAF II subsidy was lower than it would have been had the CAF II standard matched the higher RDOF minimum threshold set at 25 Mbps just two years later. Instead, fewer blocks were eligible for support under CAF II because Verizon (in theory) covered more of them at those slower but still qualifying speeds.

And it’s worth noting that while some of Plainfield’s blocks were ineligible for CAF II support because of Verizon’s claimed deployments, even these blocks would have been eligible for CAF II money if that reverse auction were run just a few months later.

Why? Well, as the residents in Verizon’s and other incumbent phone companies’ areas know all too well, DSL companies have a disgraceful history of letting these lines rot in place.

Indeed, you can see in the FCC’s deployment data how Verizon has neglected its Plainfield-area infrastructure. Blocks in which Verizon reported offering 15 Mbps as of year-end 2017 showed up a year later as having maximum speeds of 10 Mbps, then just six months later were reported as 5 Mbps-maximum blocks.

If the FCC operated the way Congress intended when it comprehensively amended the Communications Act in 1996, Verizon would have upgraded its entire network long ago, instead of breaking its promises and cherry-picking which areas it would upgrade to fiber. That history of the FCC’s failure to abide by Congress’ blueprint is informative in our current broadband-policy debates, but isn’t the subject of this post, which is the FCC’s most recent failures.

Had the agency better understood these unserved areas — both with more accurate maps and a locally informed sense of who provides broadband there and what their present plans are — it would have granted Plainfield Broadband a larger CAF II award.

These rural towns played by the FCC’s rules, and got played by them

But that’s what went wrong in 2018.

What happened in 2020? Given that Plainfield Broadband offers fiber service to every location in the town, why was Charter able to bid on and win a RDOF award for any of the town’s 92 census blocks?

The answer once again involves companies following the letter of the FCC’s rules — and the agency ignoring the situation on the ground.

The map above reflects deployment in Plainfield as of the end of 2019, a few months after Plainfield Broadband began constructing its network. The dark-blue shaded blocks are those where Plainfield Broadband was serving customers as of that date. But the FCC’s list of RDOF-eligible blocks was not based on that data; it was based on claimed deployments made six months earlier, as of June 30, 2019. The map below shows that data, illustrating that as of mid-2019, none of the town’s census blocks were served by a fixed ISP at the RDOF-minimum 25 Mbps threshold.

Westfield G&E (Plainfield Broadband’s network project manager, internet service provider, and network operator partner) did not claim all of the town’s blocks in its June 2019 or December 2019 Form 477 deployment filings, even though it knew at the time that it would very soon build out to cover the entire town. The company didn’t claim these areas because under the FCC’s rules, they were legally considered “unserved,” because Plainfield Broadband would not be able to fulfill a customer’s request within a 10-day period.

Because 28 of the remaining Plainfield census blocks were technically unserved at that specific moment in time (and were not CAF II-awarded blocks either), Charter was able to win RDOF subsidies to bring gigabit services to those blocks — which are now full of happy Plainfield Broadband customers.

With Pai gone, the new FCC must act to clean up his RDOF mess

The FCC’s ever-compounding errors create major problems for all involved.

Its failure to enforce the Communications Act left Plainfield’s residents unserved for years — with many having access to nothing but dial-up, or unreliable DSL provisioned using repurposed equipment.

The FCC’s failure to understand Verizon’s total disinterest in adequately serving its rural areas led to Plainfield Broadband receiving a CAF II award that was far smaller than it should have been.

And the FCC’s failure to understand Plainfield Broadband’s ongoing deployment activities during 2019–2020 means that Charter will receive scarce subsidy funds to deploy broadband in an area that is already fully served. Because Charter is a deep-pocketed national incumbent, it could destroy this municipal-broadband project by undercutting its prices — and then turning around and raising them well above what Plainfield Broadband charges to break even.

We hope Charter wouldn’t dream of doing any such thing — and likewise hope that if it never intended to serve this area at all, there’s a way for the FCC to reassess or for Charter to back out before money needlessly flies out the agency’s door.

The FCC isn’t obliged to continue compounding its mistakes. If Charter bid on and won these blocks without understanding what it was getting itself into, the agency should let it walk away from its RDOF commitments for these areas.

Likewise, the FCC should take a close look at all of the other CAF II areas and deal with any similar instances of double-subsidization. And there are others: As we noted above, Charter won a total of $9.4 million of RDOF awards in the census-block groups of other CAF II-funded Western Massachusetts municipal-broadband providers. The FCC should hit the pause button for these duplicative CAF II/RDOF subsidy areas, and review each to ensure that RDOF money is not being used to overbuild the original funded projects.

And the agency should review all RDOF awards granted to ISPs in densely populated urban areas, none of which should have ever qualified for rural-deployment subsidies in the first place, even when FCC maps (wrongly) showed them containing unserved customers. There’s no justifiable reason for the FCC to dole out scarce ratepayer-funded subsidies to wealthy companies to bring broadband to already-served posh urban resorts, giant airports, highway medians or empty cul-de-sac verges.