Space-X Broadband: Coming to an Empty Traffic Island Near You

Original photo by Flickr user Richard Drdul

Note: This is part three in an ongoing series. Be sure to check out the other posts:

Part 1: Fiber to the Clubhouse: Pai Subsidizes Broadband for the Rich

Part 2: Broadband Boondoggle: Ajit Pai’s $886M Gift to Elon Musk

Part 4: Ajit Pai’s Broadband Legacy: Haste and Waste

Part 5: Plan Fail: How Pai Imperiled a Rural Town’s Fiber Network

Part 6: Good News: Mass. Muni Fiber Spared from FCC RDOF Blunder

Part 7: Why Elon Musk Is No Longer Getting $886M from the FCC

Chairman Ajit Pai wants the world to think that the broadband-subsidies auction the FCC just concluded is a crowning achievement of his four years heading the agency.

The $9.2-billion Rural Digital Opportunity Fund (RDOF) is Pai’s twist on the longstanding Universal Service Fund (USF), and while the money hasn’t gone out the door the auction bidding wrapped up earlier this month.

As we have documented in our previous two posts, however, this effort to close the rural-broadband digital divide looks more and more like one of the most wasteful projects in FCC history. And that’s a tragic irony, because Chairman Pai has said his war against the Lifeline program — the FCC’s modest subsidy for low-income families — is motivated by his desire to root out wasteful spending.

When Pai lambastes Lifeline as “plagued by waste,” his examples involve cases where businesses have broken the FCC’s rules and defrauded the program. In contrast, the bulk of the waste in the RDOF program isn’t from companies defrauding the FCC: It’s from companies following Ajit Pai’s poorly designed rules.

As we’ve been careful to note in this series, rural areas are worthy of broadband support from USF. But they always get outsized attention considering that there are far more low-income people — in both urban and rural settings — who have access to broadband already but still don’t subscribe. So Free Press supports spending federal money in cities to help people afford broadband service. The question, of course, is how to spend that money.

And the answer is: not like this.

Pai has waged a multi-year crusade against Lifeline as part of the Trump administration’s broader war on the poor. But the examples he’s used to justify his sabotage of Lifeline don’t come close to the amount of money wasted in the RDOF.

The USF — and by extension, the RDOF — is funded via a regressive fee system applied to users’ phone bills. Our last post chronicled how Elon Musk’s satellite-broadband venture Starlink and a few other companies won your money to serve airports and parking lots in densely populated, well-served urban areas. Below are more examples of Musk’s curious and nonsensical winning bids in cities; we’ll focus on other ISPs’ awards in non-urban areas in future posts.

Zooming in on waste

Our first post featured examples of questionable funding in urban areas. We stumbled upon these after spending a few minutes with the map of winning bidders. Our initial estimates indicate that more than $700 million of RDOF money is being spent to deploy service to already well-served urban census blocks, and our research suggests there’s ample waste in the rural blocks too. Our second post focused on eyebrow-raising subsidies granted to Musk’s soon-to-launch satellite-broadband company, Starlink, which received $886 million in subsidies, with $111 million of that meant for urban areas.

Though Musk’s fans and one or two random people on Twitter are suggesting that we’re cherry-picking the worst cases, the reality is just the opposite. Since the FCC’s RDOF awards encompass nearly 60,000 census-block groups containing nearly 800,000 census blocks, uncovering these examples doesn’t require cherry-picking: Just pick any urban or suburban area and zoom in.

We continue to find questionable RDOF grants everywhere we look.

Why are we giving Elon Musk rural-broadband subsidies to serve a downtown Philly university?

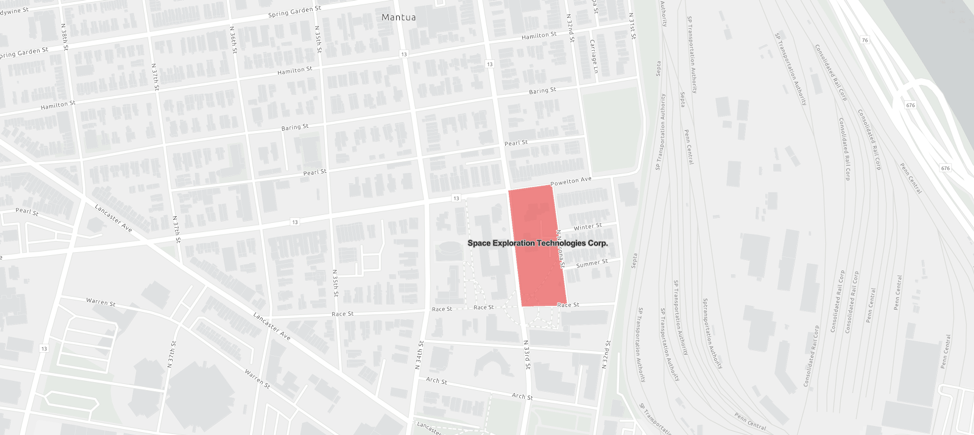

Musk was awarded funds for this block in Philly. It has just one property, a Drexel University English-department building. According to the FCC’s broadband map, the only “fixed” (as opposed to mobile) broadband available here is Verizon’s 15 Mbps DSL. But literally across the street Verizon offers FiOS and Comcast offers its gigabit-cable service.

Cooperative Network Services, LLC

So is the Drexel English department getting by on slow DSL? Of course not.

Drexel has its own campus-wide wired and wireless infrastructure, which is surely why Comcast and Verizon didn’t deploy to this single structure even though they did pretty much everywhere else in the surrounding area. (We called the publicly listed telephone number for this Drexel building and left a message. We haven’t heard back, because some random person asking “do you have internet?” probably sounds like the 2020 version of “is your refrigerator running?”).

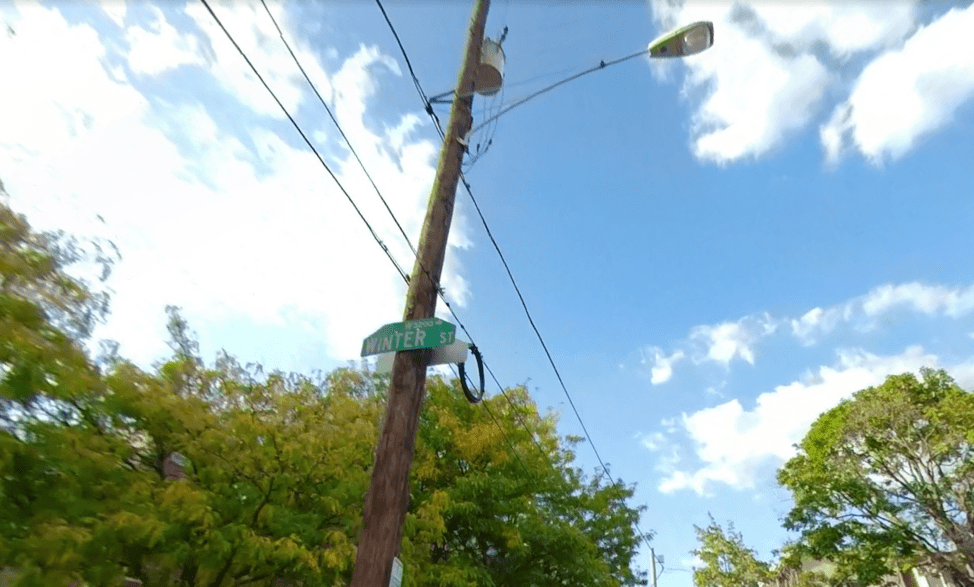

We can visually confirm that this block should meet the FCC’s technical standard for a “covered” block. Look at the picture below: That little coiled-up loop of wire on the utility pole sure looks like Verizon’s fiber line, and it appears Comcast’s high-speed coaxial cable is right across from it.

Cable and telecom network coverage is often described in terms of homes passed — meaning not that they were passed by or left out, but that the companies’ wires really do pass right in front of the building in question. There’s no disputing that this city block is already passed by the networks of two gigabit providers, and therefore should not have shown up as an eligible RDOF block.

Starlink should not have been able to win subsidies to “deploy” its satellite-broadband service here (itself a funny concept, because there’s no way a satellite service could deploy to and serve a single building rather than a much bigger geographic area). But because Drexel doesn’t buy service from commercial ISPs, and because the commercial ISPs didn’t claim this block as one they served, Musk could be paid to do absolutely nothing here.

Why are we giving Elon Musk rural-broadband subsidies to serve a downtown Philly Amtrak station?

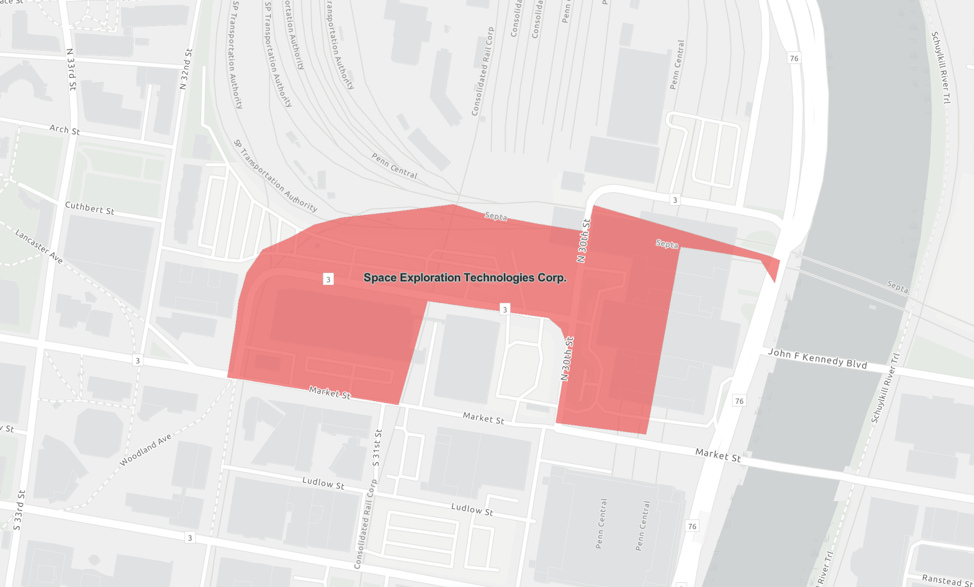

A couple of blocks away from Drexel’s English department are more university and industrial properties. Here Musk won a $21,344 subsidy to serve 43 customer locations. This collection of census blocks (shown as a block group below) show up in the FCC’s database as RDOF-eligible blocks, with apparently no fixed service at all.

What’s located here? The part on the left side of the “n” shape is Drexel property (One Drexel Plaza). The top of the “n” shape is parking lots and a rail yard. Across from 32nd Street on the right side of the “n” is the Amtrak 30th Street Station. Right between the two properties (inside the “n”) is a census block where Verizon reports offering FiOS gigabit-fiber service. That’s likely the case because non-Drexel offices are located on that parcel of land, and Verizon was able to serve them since they’re not served by the university’s IT department.

The incumbent ISPs’ failure to claim these census blocks is the only reason the FCC allowed Starlink to bid for them. We’re not sure why Verizon didn’t claim them; this understating of urban deployment appears to be a widespread problem in the FCC’s data. The agency’s maps are routinely criticized for overstating coverage — and often they do — but we can see here that the opposite error is a problem too if areas are marked as “unserved” only because of ordinary circumstances like this.

Whatever the root cause of the issue on the maps, it’s a certainty that Drexel University and Amtrak have no need to buy Starlink’s service, and Starlink has no intention of even trying to sign them up as customers.

Cooperative Network Services, LLC

Why are we paying Elon Musk to deploy satellite broadband to giant storage tanks in an urban industrial park?

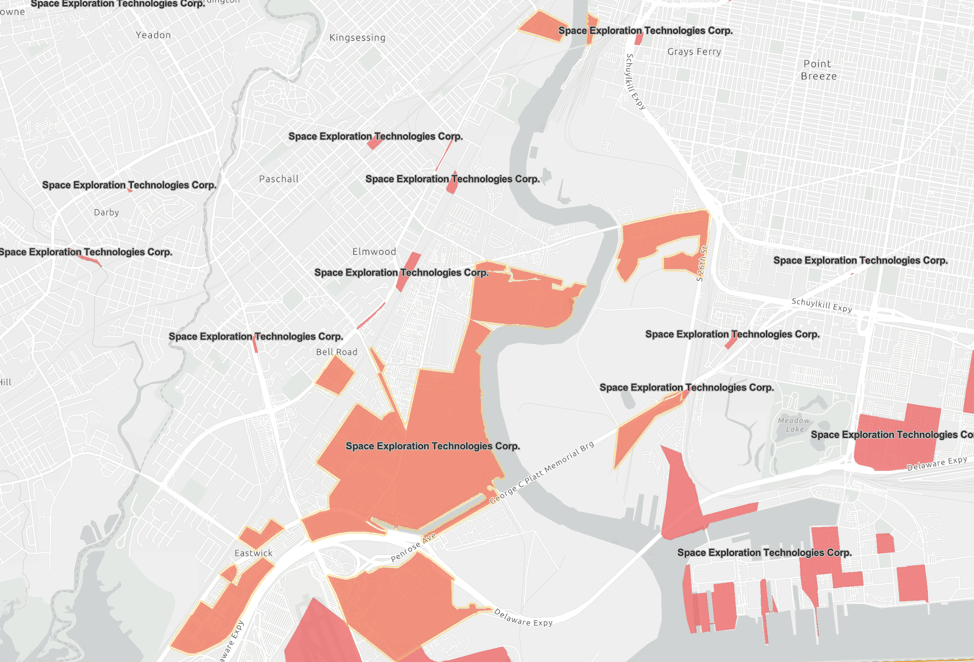

Let’s float down the Schuylkill River to check out more of the many “unserved” areas where the FCC is handing your money to Elon Musk. First up is a group of census blocks that contain a reported 144 customer locations — and that the FCC awarded Starlink $97,152 to serve.

Cooperative Network Services, LLC

So what’s here? The satellite view confirms what locals and travelers past the airport and on I-95 may already know: This is a very industrial area. Look at all those storage tanks!

But according to Form 477, the FCC form that ISPs use to provide data about their service areas, some of these blocks actually have Verizon xDSL services. So unlike some of the blocks housing Drexel University — which showed up in the data as areas completely bereft of fixed ISPs — we see here that the incumbent hasn’t met the broadband-speed standard that would make these blocks ineligible for USF deployment funds.

But does that mean these blocks should qualify for subsidies? Of course not!

A block in an urban area is not like a block in a rural area. The reason rural areas lack broadband despite demand is that the per-home cost to deploy service is just too high for a carrier to earn its desired rate of return. In many unserved rural areas, even the most altruistic ISP couldn’t keep the lights on while charging a semi-reasonable rate for broadband without government subsidies.

But in an urban area, there may be a host of reasons why a block has Verizon DSL but not fiber or cable-modem service. Those tanks above and the auto-parts store next door might not actually need anything more than 10-15 Mbps DSL. Maybe Verizon and Comcast rightly calculated that there’s no need to spend the money to “pass” that property with gigabit service. Or maybe these industrial areas get broadband from some private-carrier service that doesn’t show up on the FCC’s map.

But that doesn’t mean it would be so expensive for Verizon to extend faster service to this area that the company would need federal dollars to cover properties located so close to its existing network and customers. Whatever the reason, it’s completely unjustified to give rural-subsidy dollars to a satellite-broadband company for these areas.

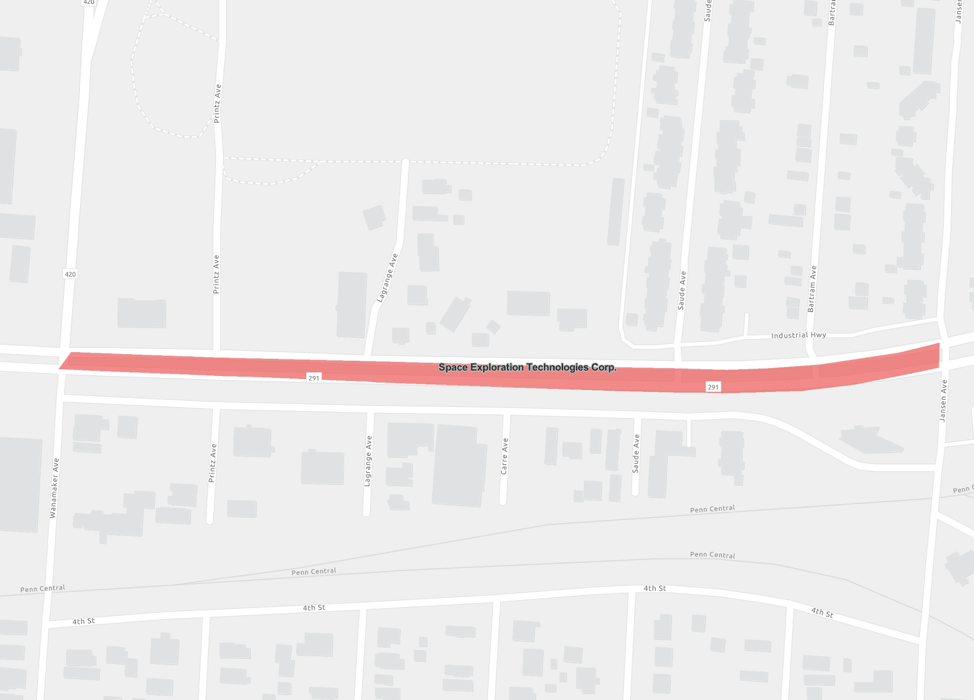

Why are we paying Elon Musk to deploy satellite broadband to highway medians and empty patches of grass?

It’s not all buildings owned by big companies, universities and institutions. Spend any time with the RDOF winners map, and you’ll quickly stumble upon some real head-scratchers. One of the more perplexing phenomena is the award of RDOF funds to deploy broadband to busy roads with no obvious physical buildings on them — and which are surrounded on all sides by existing gigabit deployments.

Here’s one of the many examples of short segments of road with no apparent buildings of any kind that were somehow eligible for RDOF funds. This road is right outside the Philly airport. The businesses on either side sit on their own census blocks, and have multiple options for super-fast broadband.

But because no fixed ISP claimed to serve the road — which is a flaw in the FCC’s administration of its rules — the two blocks that cover just the road segment became eligible for RDOF subsidies, and Starlink won the bidding. We’ve stared at the map of this road segment for a while, and can’t figure out why the FCC thinks there are eight customer locations here. Maybe it counts parking meters?

Regardless, that means $5,772 of your money is going to Elon Musk to do absolutely nothing.

Cooperative Network Services, LLC

To reiterate, finding such examples doesn’t require cherry-picking. The Philly area is full of USF-funded stretches of roads and medians. Here’s one on the Pennsylvania Turnpike, surrounded on all sides by multiple gigabit ISPs. The FCC thinks there are three customer locations here, so it’s paying Musk $948 to serve it, even though there’s nothing here but six lanes of highway and a thin concrete barrier.

Naysayers may try to downplay these road examples as amounting to very little, because the FCC’s auction system determined many of these blocks contained only a handful of customer locations, keeping the total award down. Well, the FCC’s predictions about how many potential customers are in these areas are not always accurate.

Here’s a super-small segment of a street next to a public park, all located near the 30th Street station, the zoo and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. This is not a remote or sparsely populated place. The FCC said this bit of road and sidewalk next to the park (which has FiOS gigabit service) contains a whopping 43 customer locations! That means the FCC is giving Musk $21,340 raised from fees on your cellphone bills to serve this supposedly needy area.

Sometimes it’s not even a typical road median, but a few square feet of grass. Look at this one! This little tiny piece of land is a cul-de-sac in the Philly suburb of Wynnewood. It is a unique census block, served on all sides by Comcast and Verizon gigabit. But because those ISPs didn’t claim this clump of bushes and trees that the FCC thinks contains three separate customer locations, Musk will pocket nearly $1,000 for saying he’ll offer service here.

Local birds are ecstatic.

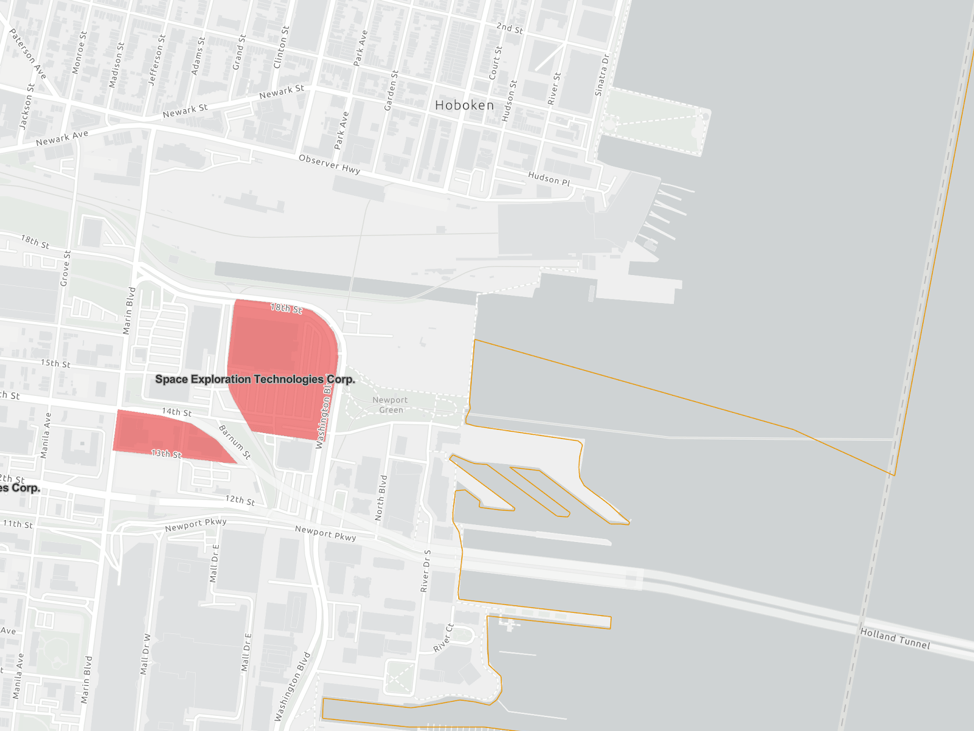

Why are we paying Elon Musk to deploy satellite broadband to big-box stores, jogging trails and parking lots in the densely populated New York metro area?

The “R” in RDOF stands for rural. And Elon Musk’s Starlink is a product specifically designed for and marketed to customers in remote rural areas (the price, well above the median-broadband price, makes it clear this is an option of last resort).

Despite that, Starlink bid for and won subsidies in many of the most-densely populated urban areas in the United States. According to the Census Bureau, 10 of the 11 most-densely populated towns and cities are located in the New York metro area. Many are on the New Jersey side of the Hudson River right across from Manhattan. Many communities in this area need broadband-adoption subsidies, but there’s no need whatsoever for broadband-deployment money.

Here’s a block on the northern edge of Jersey City where Starlink won an $8,380 RDOF award. This block, which is a few feet from Comcast and FiOS-served luxury condos overlooking the Hudson River, is home to the Jersey City Target. It would seem odd that there’s a business case for Comcast, Verizon and another ISP called “Nuvisions” to serve the surrounding blocks but not the Target. It would also seem odd to think that Target is just making a go of it using commercial Verizon 10/1 DSL, but maybe?

Whatever the reason this Target ended up on the RDOF-eligible list, there’s no defensible case for Elon Musk to get a single penny for this area.

Cooperative Network Services, LLC

Starlink didn’t win any RDOF money for Manhattan, because the FCC’s data considers every block there to be fully served. But the other boroughs are full of questionable Musk-winning locations.

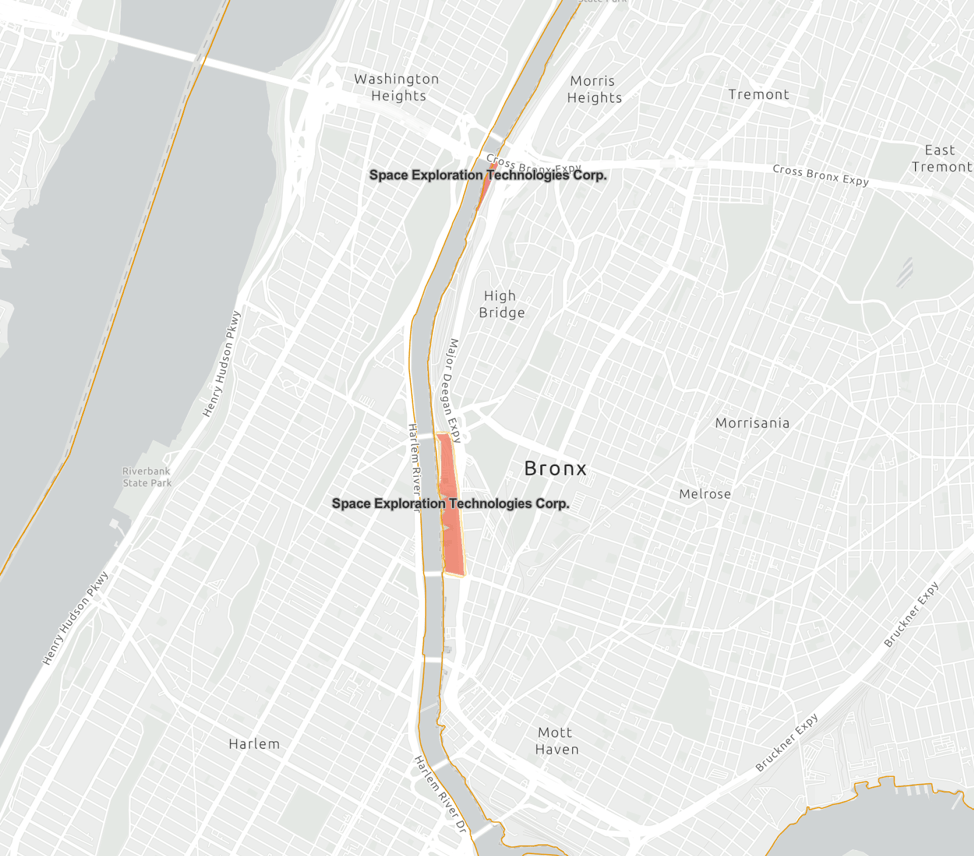

Here’s a sliver of “underserved” land sandwiched between the Harlem River and the Major Deegan Expressway in the Bronx. According to Form 477, Verizon offers only 15 Mbps DSL here, so Musk’s Starlink bid for and won a $24,868 subsidy to supposedly offer service to the nine customer locations here.

Looking at the map, we’re not quite sure what those are other than a tennis court and a children’s museum. The museum of course needs good internet access, but according to its website, this location is just where its mobile bus parks.

Regardless, Verizon offers gigabit fiber literally a few feet away from these blocks, to the north, south and east.

Cooperative Network Services, LLC

There are all sorts of examples like this. The tinier bit of red in the picture above contains two more census blocks Musk is being paid $3,176 to serve. We’re not sure what’s there that needs satellite internet. It looks like a parking lot with maybe one shed.

Will Elon defend any of this?

These examples raise some serious questions about the FCC’s program. But to be fair, Ajit Pai’s track record never inspired much confidence in the first place. He rushed this 10-year RDOF auction out the door, ignoring explicit pleas from the agency’s two Democratic commissioners to slow down and get it right.

Well, he didn’t listen and now we’re seeing the consequences of Pai’s hubris, though it’s something he won’t be around the FCC to deal with.

So what can be done now? Free Press is currently exploring all options. The simplest recourse is for Elon Musk — one of the world’s wealthiest people — to admit this is a misuse of public funds, and refuse to accept these subsidies.

To be clear, we didn’t set out to pick on Musk or Starlink. Assuming everything goes to plan, we have no doubt the service is going to end up helping connect lots of rural families. But Musk and Starlink don’t need our help to do that, especially not when the money derives from bizarre awards for urban slivers that don’t need any subsidies at all (much less for a satellite service like this).

And there are plenty of other ISPs that deserve to be shamed for dubious RDOF awards. Some of these bids serve similar patches of concrete and well-connected urban areas. Others appear to have won RDOF awards to serve already-connected rural areas, some of which were recently brought online in part thanks to Obama-era FCC subsidies.

We plan to explore these facets of the RDOF mess in the days and weeks ahead. Stay tuned.