Tall Tales and Title II

Original image by Flickr user Verkeorg

A rural ISP’s CEO told Congress that Title II and Net Neutrality stopped his network investments. That’s not true. Here we break it down.

With a new Congress and new House majority leadership come new hearings on old topics.

First up in the media space was a House Energy & Commerce Communications and Technology Subcommittee hearing on Net Neutrality (the official title was “Preserving an Open Internet for Consumers, Small Businesses, and Free Speech”).

The hearing was welcome to be sure. It put the spotlight back on the need for someone — Congress or the courts at the moment — to restore all of the communications rights FCC Chairman Ajit Pai ripped away when he repealed the FCC’s strong 2015 Net Neutrality rules. Our own Jessica J. González testified at the hearing about the real-world impacts of losing those protections.

But the hearing produced lots of other moments to dissect, and lots of misstatements — by other witnesses and some lawmakers — to investigate and correct. Free Press has expended substantial time analyzing the issue of FCC policies’ impact — or rather, lack of impact — on broadband-industry deployment and investment. So the claims from hearing witness Joseph Franell — the general manager and CEO of Eastern Oregon Telecom (“EOT”) — stood out like a sore thumb.

In his testimony, Mr. Franell said “The application of Title II as part of Net Neutrality had a dramatic chilling effect on rural telecom in the Pacific Northwest and I suspect the same could be said about the rest of the country.”

He also said that since the repeal of the 2015 FCC Order, “investors have been much more willing … to invest in rural telecommunications,” asserting that his company “has been able to focus on continuing to provide exceptional telecommunications and is currently expanding into other markets that are underserved.”

This claim struck us as bizarre, chiefly because all of the available data show the exact opposite occurred.

Across the ISP industry, both large firms and small ones like Mr. Franell’s kept right on investing under Title II: expanding their coverage, increasing their speeds and improving their networks. In fact, back in December 2017 and right before the Pai repeal, we thoroughly debunked similar claims made by five other rural ISPs who claimed — falsely — that the Net Neutrality rules had prevented them from investing.

So we decided once again, as the kids say, to check the receipts. And unfortunately for Mr. Franell, the numbers on Eastern Oregon Telecom — and his own prior statements to the media — don’t match up with the far-fetched claims he made at the hearing.

The D.C. debate about broadband investment routinely focuses on the wrong things

Everyone knows that ISPs don’t want the FCC to have authority over aspects of their business. But most industry observers also understand that the broadband industry’s grousing about Title II and Net Neutrality, before the FCC adopted the 2015 rules, completely faded away after the February 2015 vote.

In fact, after that vote took place, ISP-industry deployment and upgrades continued at a remarkable pace.

Cable companies large and small led the way by rolling out the next technical standard for their systems (called “DOCSIS 3.0”) and deploying fiber lines closer to their end-user customers. Telephone-company ISPs large and small finally began widespread upgrades of their antiquated DSL lines (a variety called “aDSL”), moving to newer higher-capacity technologies such as “aDSL-2/2+,” “VDSL,” and fiber-to-the-home (“FTTH”). Fixed-wireless ISPs, which tend to focus on niche customer segments that are either in rural areas or dense urban areas, rolled out significant upgrades.

The debate about the practical impact of the restoration of Title II and the adoption of Net Neutrality rules focuses far too much on the concept of “investment” without measuring it properly. One way of measuring it is to look solely at the sheer dollar amount of capital expenditures ISPs make, because network infrastructure is a capital good. That focus on capital investment is unfortunate, though, for a few reasons.

First, because of the human need for simplicity, politicians and reporters tend to focus on various estimates of the ISP industry’s aggregate capital spending and how that changes from year to year. This focus on aggregate investment is unfortunate because summing up all of the spending by every publicly traded firm is prone to methodological abuse, but it also masks the much more informative data that we can observe at the individual company-level.

It’s also unfortunate because the focus on short-term changes in capital spending ignores why a given company might have spent more in one year and less in the next. Those interested in the truth can go to the primary sources to understand why spending changes (and in so doing learn that the ISPs themselves universally indicated that the FCC’s Title II and Net Neutrality policies had no impact — one way or the other — on their investment decisions).

But the focus on the amount of money spent on capital equipment is also unfortunate because how much a company spends isn’t what we should be worried about — and it’s not the outcome Communications Law is concerned about either.

Our nation’s official policy is to promote deployment of affordable, high-quality broadband telecommunications services. If the industry goes through an upgrade cycle and spends a little less on capital equipment during the period before the next upgrade cycle comes along, that’s not a policy failure. If technology improvements make capacity expansion less expensive than it was previously, that also isn’t a policy failure. What matters is what’s available for people to subscribe to, and how much it costs them to subscribe.

The most frustrating aspect of this investment-impact debate is the oversimplification of cause and effect.

Last week’s hearing might have given the impression that it’s actually possible to know the impact of Title II’s restoration on deployment simply by knowing if aggregate-industry investment went up or down after 2015. That’s a fallacy, and it’s entirely specious reasoning.

Just as Lisa Simpson was able to “prove” the efficacy of her magic anti-tiger rock by pointing out the absence of tigers to her gullible father, FCC Chairman Pai has been eager to use manipulated industry-aggregate investment data to prove the alleged harms of Title II on broadband investment (hoping, of course, that no one notices his aggregate data are inaccurate; that far more ISPs increased capital spending under Title II than the few that declined for unrelated reasons; that deployed capacities increased sharply under Title II; and that numerous ISPs specifically said Title II had no impact).

Who are you going to believe? The witness, or your lying eyes?

Back to our hearing witness and his problematic claims.

Eastern Oregon Telecom isn’t a publicly traded company, so we’re unable to look at any Securities and Exchange Commission filings to see how its capital spending fluctuated between the period before and after the 2015 Net Neutrality vote. However, we do have a few other useful tools: an internet-search engine, and FCC broadband-deployment data.

Twice a year all ISPs are required to tell the FCC where they offer service, at a very granular level (the geographic boundary of a census block). This so-called “Form 477” deployment data is thus a great source of information to understand what happened in terms of deployment after Title II’s restoration.

While looking at any changes in available capacities and deployment can’t teach us anything about why they changed, we can use it to evaluate the validity of Franell’s claims that Title II’s restoration caused a “chilling effect” on his ability to expand and improve EOT’s networks.

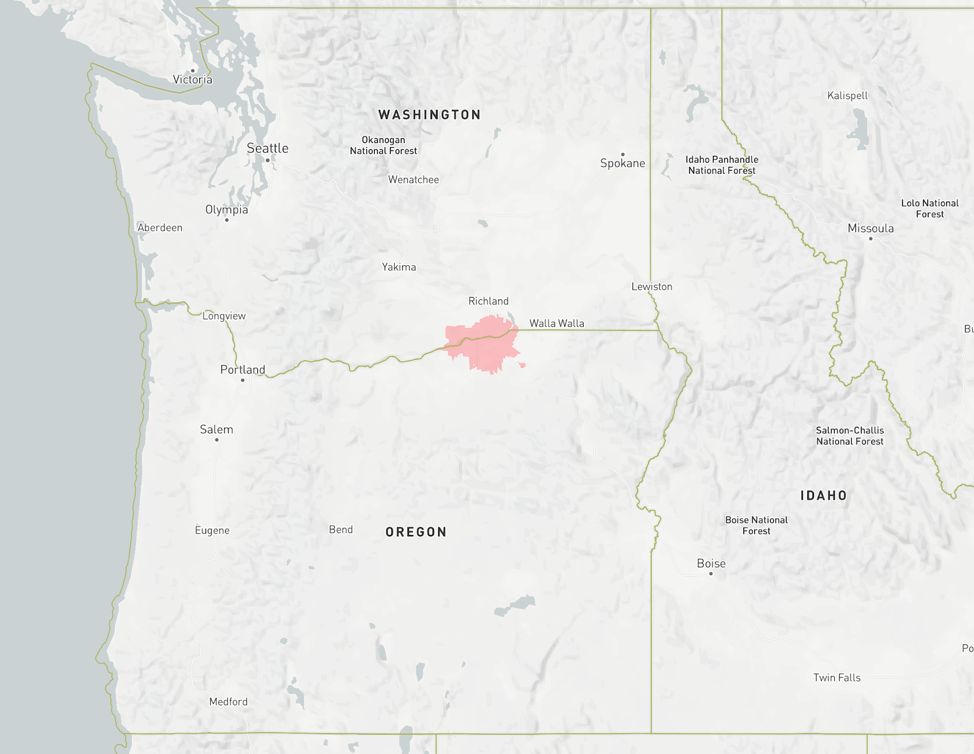

EOT is a small ISP that serves its customers along the Columbia River in north-central Oregon and south-central Washington State (see the map below). It uses a mix of technologies to provide broadband: cable, traditional telecom (aDSL lines in this case), advanced telecom (FTTH), and fixed wireless.

Two-thirds of the territory that EOT serves lies in rural census blocks, but rural blocks are (by definition) sparsely populated, so only about one-fifth of the people living in EOT’s service area reside in these rural blocks.

Figure 1: Eastern Oregon Telecom’s Service Area

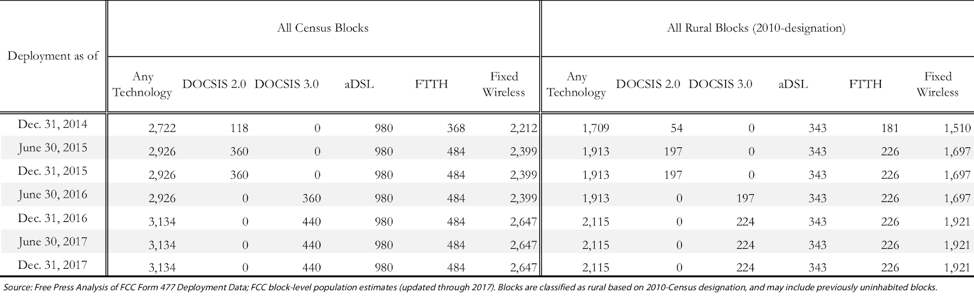

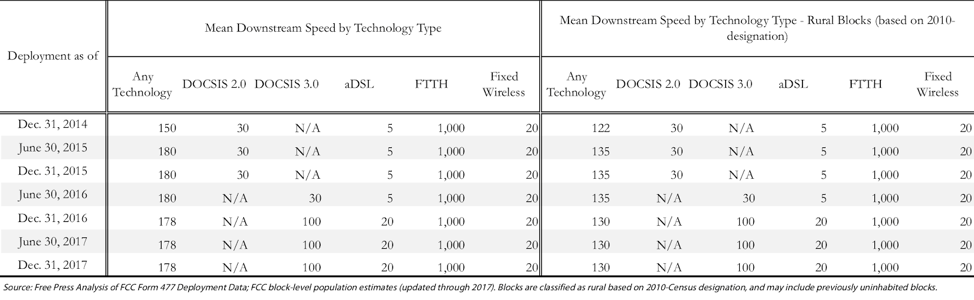

We examined Eastern Oregon Telecom’s FCC Form 477 deployment data for all seven reporting periods that the FCC collected this data during the time period in question at the hearing:

-

Dec. 31, 2014 (two months before the FCC’s Title II and Net Neutrality vote)

-

June 30, 2015 (four months after the vote)

-

Dec. 31, 2015 (nearly a year after the vote)

-

June 30, 2016 (nearly one and a half years after the vote and ahead of the 2016 elections)

-

Dec. 31, 2016 (nearly two years after the vote and the first reporting for deployment that occurred in part after the election)

-

June 30, 2017 (the first reporting after Chairman Pai started the process of repealing Net Neutrality)

-

Dec. 31, 2017 (the first reporting period after the repeal)

Here’s what we found.

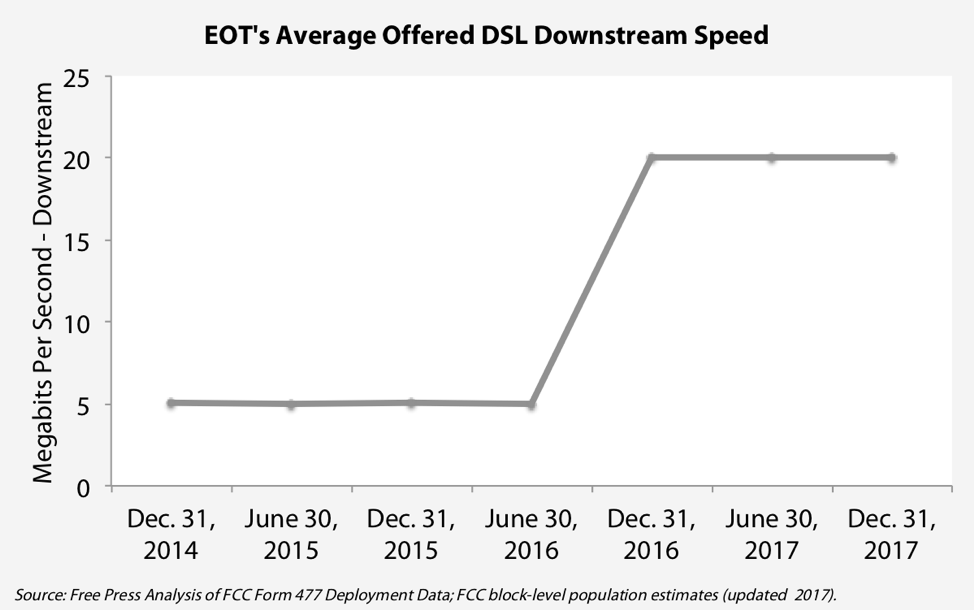

After the FCC restored Title II authority and adopted Net Neutrality rules, Eastern Oregon Telecom significantly expanded its broadband deployment. Despite its CEO’s claims of a chilling effect, his company’s deployment data suggests otherwise.

For example, while under Title II:

-

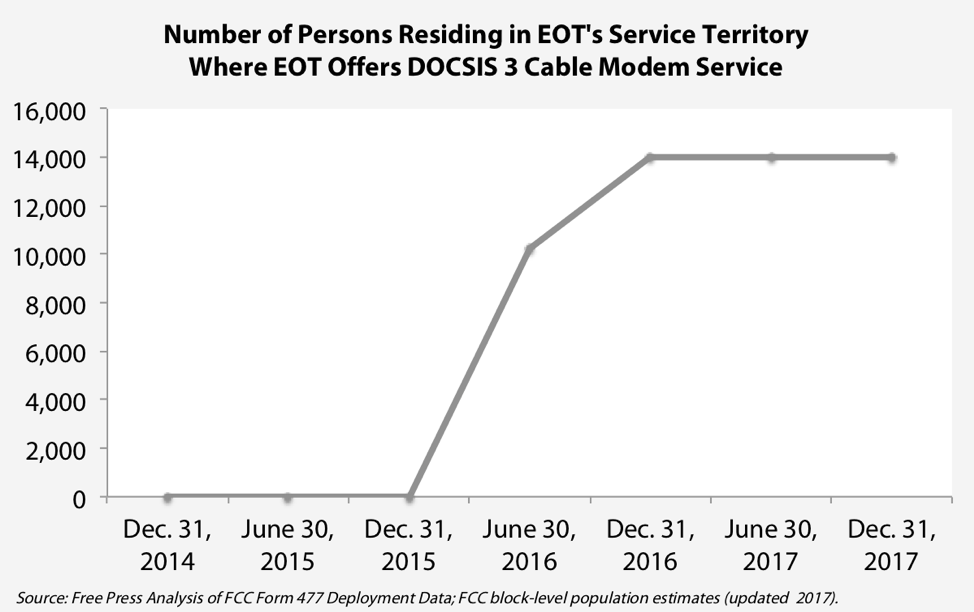

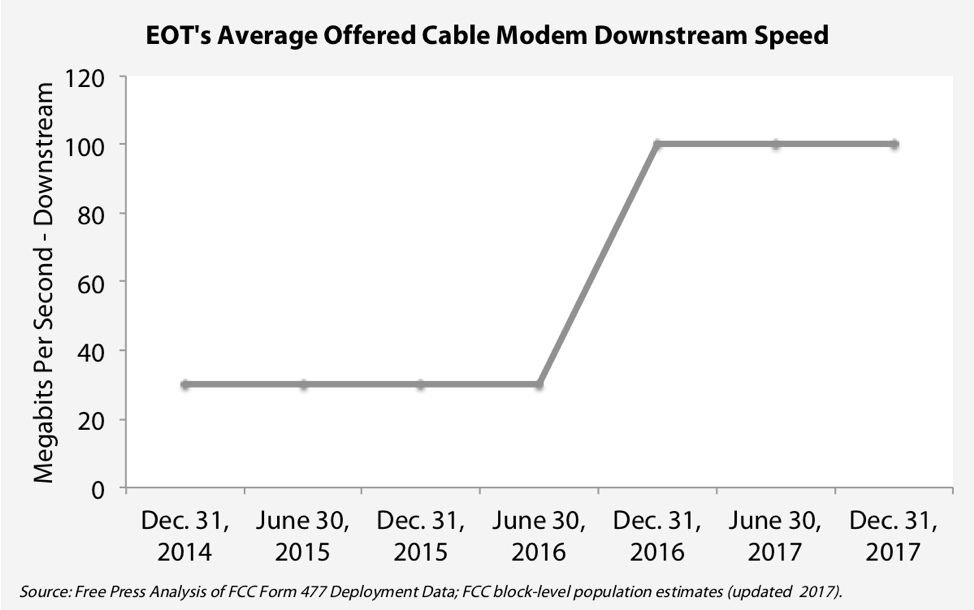

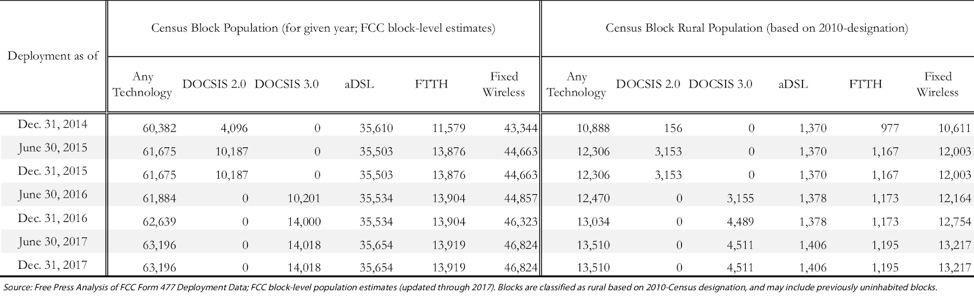

EOT substantially expanded its cable-system footprint into previously unserved areas; upgraded 100 percent of its cable lines from the old DOCSIS 2 standard to the higher-capacity DOCSIS 3 standard; and more than tripled the marketed downstream speeds of all of these cable-modem lines from 30 Megabits per Second (“Mbps”) to 100 Mbps.

-

EOT quadrupled the capacity of all of its DSL lines, from a maximum downstream capacity of 5 Mbps to 20 Mbps.

-

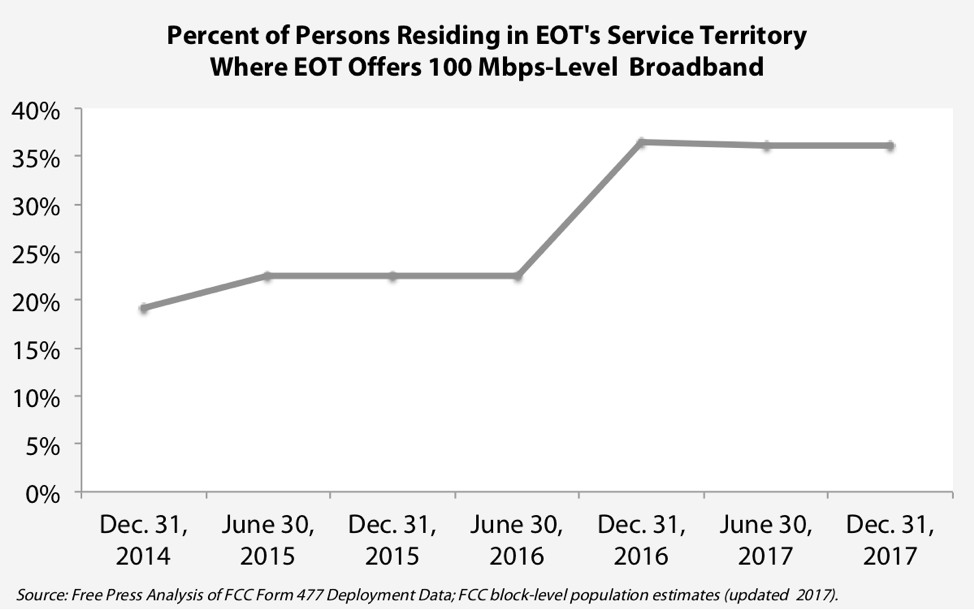

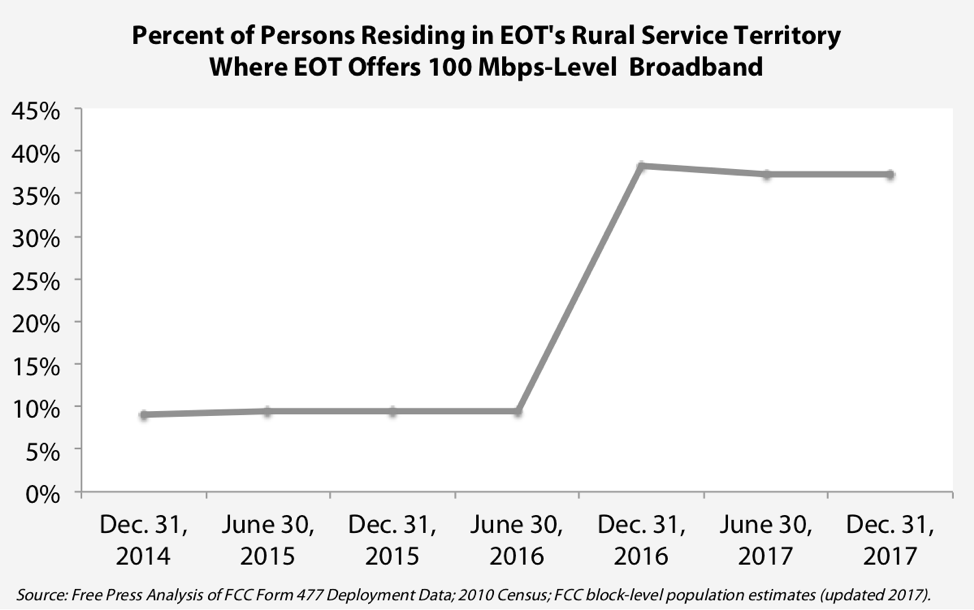

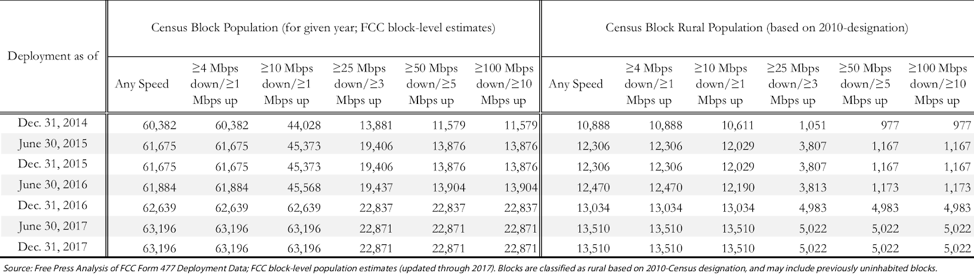

Between the end of 2014 and the end of 2016, the number of people living in a census block where EOT offers the FCC’s minimum standard of 25 Mbps downstream/3 Mbps upstream increased by 65 percent.

-

Between the end of 2014 and the end of 2016, the number of people living in a block where EOT offers 100 Mbps downstream/10 Mbps upstream (or even higher-level service) nearly doubled.

-

The number of blocks where EOT offers fiber-to-the-home service increased by 31 percent between the end of 2014 and the end of 2016.

-

The number of blocks where EOT offers fixed-wireless service increased by 20 percent between the end of 2014 and the end of 2016.

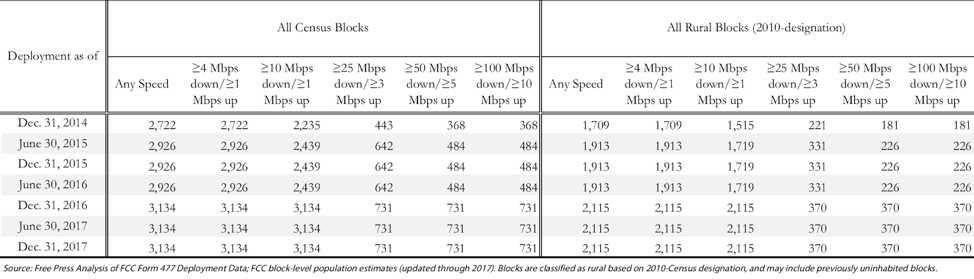

Overall, between the end of 2014 and the end of 2016, EOT expanded the total number of blocks it served by 15 percent (from 2,722 blocks to 3,134 blocks). But a substantial number of EOT’s deployments and upgrades made during the restored Title II era were in areas classified as rural or unpopulated blocks as of the 2010 Census.

-

Between the end of 2014 and the end of 2016, EOT expanded the total number of rural blocks served by 24 percent (from 1,709 blocks to 2,115 blocks).

-

The number of rural blocks where EOT offers cable-ISP service increased by 315 percent between the end of 2014 and the end of 2016.

-

The number of rural blocks where EOT offers FTTH service increased by 25 percent between the end of 2014 and the end of 2016.

-

The number of rural blocks where EOT offers fixed-wireless service increased by 27 percent between the end of 2014 and the end of 2016.

-

The number of rural blocks where EOT offers downstream speeds at or above 100 Mbps increased by 104 percent after Title II’s restoration.

Below we present some figures showing the impressive improvements EOT made after the FCC returned to Title II in 2015, followed by detailed tables summarizing the data.

The internet never forgets

In 2015 and 2016, EOT’s CEO repeatedly touted his company’s “model” rural-fiber investment program, a project announced and expanded after the FCC restored Title II.

The deployment data presented above paint a clear picture of an ISP with plenty of confidence about its business. But while numbers never lie, EOT’s contemporaneous statements provide further clarity. And it didn’t take much digging to find numerous examples of Mr. Franell singing a far different tune during 2015 and 2016 than the one he belted out in his recent testimony.

In March 2015, just a few days after the FCC’s historic vote returning to Title II, EOT and Chinese telecom-equipment firm Huawei put out a joint press release announcing a new fiber-to-the-premises deployment project that would bring gigabit service to “over 8,000 homes and businesses in Hermiston and the surrounding area.” The release indicated initial deployment would take place in late 2015, continuing into 2016.

The same day Mr. Franell gave an interview with the Portland Business Journal about the project. He said it would cover between 6,500–6,700 households, and that EOT “expects to invest $2 million” on the project.

Now, such projects take time to plan, and Mr. Franell revealed that this one had been two years in the making. He indicated that the March 2015 announced expansion came after a successful pilot project conducted in 2014.

If EOT and Mr. Franell were feeling the “chilling effects” of the Title II decision, he certainly had time to pull the plug on the project and save himself the additional $2 million in investment costs. But the FCC’s vote — the topic of the day in D.C. telecom-lobbying circles — was totally absent in these 2015 interviews.

Read the interview conducted in June 2015, three months after the FCC voted to restore Title II and just days before the strong Net Neutrality rules took effect. Franell still sounded buoyant about his project, telling the outlet Telecompetitor “when we finish this, [Hermiston] is going to have better [internet service] than most places in the United States.”

When asked about challenges EOT faced as it deployed all this fiber, Franell didn’t mention regulation or regulatory authority; he said his biggest obstacle was just explaining to people what his new gigabit service was, and why it would be useful to them.

EOT’s fiber investment is a success story, even more so when you consider that this ISP isn’t a cable- or telephone-company incumbent.

EOT was formed from a collection of utility cooperatives, and is technically an “overbuilder,” competing against CenturyLink and Comcast in areas where those giant companies had already built out networks. Overbuilders like EOT face much more difficult deployment challenges than incumbents: They don’t qualify for most federal subsidies, and they have to compete against deep-pocketed national conglomerates.

If Title II really had the chilling effect Mr. Franell is now saying it did, EOT would have been one of the first ISPs to curtail deployment. But it didn’t curtail deployment. In fact, over a year after the FCC’s Title II vote, EOT told the media that it was expanding its fiber-buildout plans.

In early 2016, the outlet East Oregonian reported that EOT’s Franell still believed “there’s room for growth in the Hermiston fiber market” and that EOT wanted to “expand smartly.” The story also reported that “[l]ess than two years into offering fiber, EOT is breaking even on its investment.”

That’s an impressive result by any standard, reflecting the reality that economics, not unfounded fears about potential regulation, drives ISP-industry investment decisions.

In April 2016 — over a year after the FCC’s vote — EOT told the Hermiston Herald that it had “identified 10 possible zones in the city to expand its fiber-optic network to more homes and businesses,” and that it had set up a Google-Fiber-style website where potential customers could tell EOT they would sign up if the firm deployed gigabit to their neighborhoods.

Franell told the paper that the response to the 2015 first phase of deployment “has been great,” and that EOT was “excited to offer more homes and businesses in Hermiston the opportunity to get ultra high-speed Internet with excellent customer service at competitive rates.”

Finally, EOT’s CEO is a member of the Oregon Broadband Advisory Council (or “OBAC”). In October 2014, while the FCC was in the midst of a very public debate about Net Neutrality and Title II reclassification, the OBAC issued a draft report on broadband deployment and adoption in the state.

Though the report referenced the FCC more than 60 times, it never mentioned the open-internet proceeding or Title II. When the OBAC submitted its final report to the Federal Broadband Opportunity Council in November 2016, it mentioned the existence of the Net Neutrality rules and Title II classification, but didn’t reference them in any of its 12 recommendations. In fact, it didn’t mention the FCC’s 2015 policy in any negative light or in conjunction with the topic of investment.

Summing it all up

The small ISP telling Congress that Title II harmed its investments actually expanded coverage and increased speeds remarkably with Title II in place.

We have no idea exactly what went on behind closed doors at EOT as it made decisions about the impact of FCC policy on its plans. At the hearing, Franell talked about his inability to get a loan, but presented no evidence that any lenders turned his company away or, if they did, why they did. Given the depth of the fact-free fearmongering surrounding the impact of Title II’s restoration on the future prospects of the ISP industry, it’s certainly possible that a loan officer who isn’t well-versed in the details of communications policy might have concerns.

But the burden for providing an honest explanation of the actual impact of this particular FCC policy is on EOT and other ISPs. If after needlessly fanning the flames of fear about the FCC’s rules they found themselves unable to access debt markets, that’s an irony and a result they’re responsible for.

However, the deployment data EOT submitted to the FCC under penalty of perjury strongly suggests that the company itself had plenty of confidence in its business under Title II.

Though some of EOT’s upgrades came shortly after the 2015 vote, the bulk of its system upgrades came during the second half of 2016, at a time when the policy’s impact was clear (and at a time when many believed voters would elect a Democratic president and thus keep in place an FCC that would maintain the 2015 policy framework).

And the numerous media reports and interviews Mr. Franell gave in 2015–2016 directly contradict his claims in the hearing. Those reports indicate that EOT did invest $2 million in new money on fiber deployment after the FCC’s vote, a project it expanded after living under restored Title II for over a year.

Indeed, according to its FCC filings, EOT made no further system upgrades in 2017. That doesn’t mean that more aren’t forthcoming: Technology deployment is cyclical, after all. But it also shows that the company did expand broadband coverage and increase speeds when Title II was back in place, and then stopped after Ajit Pai promised to gut the Net Neutrality rules and abandon his agency’s authority over ISPs.

EOT’s written testimony is much more carefully constructed than the verbal responses its CEO offered in last week’s hearing. But the message from both was clear, and deeply misleading.

We hope the lawmakers who listened to EOT’s claims about how Title II allegedly harmed its network deployment closely measure them against the only available data on those deployments and EOT’s contrary statements when Title II actually was in place. The numbers don’t support EOT’s tales of woe when judged against the historic levels of improvements the company made to its services under the 2015 rules.